Rabbi Fishel Jacobs: How Memorizing Tanya Saved My Life

From Beis Moshiach Magazine: Today, Rabbi Fishel Jacobs is a world-renowned posek, author, lecturer, and educator. In this personal monograph, he tells of his formative years in Tomchei Tmimim and of how memorizing the holy letters of the Tanya saved his life • Special for Yud-Tes Kislev • Full Article

By Rabbi Fischel Jacobs, Beis Moshiach Magazine

I thought it would be a good idea to write up the following story because of two reasons. The first, because over the years I’ve been asked about it. The second, to strengthen the ancient tradition of reviewing the words and letters of Tanya by heart. So, I will tell you the role they played in my story.

BEREISHIS

When I grew up in America, we did not keep kosher at home, nor did we observe Shabbos or holidays. I put tefillin on only once, at age sixteen, when visiting the Kosel.

My initial involvement in a life of Torah and mitzvos began when I was a student. I was visiting 770 where I R’ Moshe Naparstek z’l, who was a celebrated mashpia in the yeshiva in Kfar Chabad. We hit it off and when I went to Kfar Chabad he was my mashpia and supervised my growth.

I went to the yeshiva in Kfar Chabad for the first time in 5737. As expected, I was sent to the yeshiva for baalei teshuva. By that time, I had finished three years of college and my first year in yeshiva gave me the credits for my degree. At that time, when I was 21, I was at the height of a ten year career in competitive sports.

ALL BEGINNINGS ARE DIFFICULT

When I first entered yeshiva, I was euphoric. I remember the moment I entered the big room called the zal. I held my suitcase as I examined the sefarim. “For the first time in my life I will open Gemaras, sifrei Chassidus, Shulchan Aruch,” I marveled. Within a short time, I was confident, I would master the material in them.

I wasn’t familiar with the term “talmid chacham,” but I imagined I would be one. The justification for this assumption was based on my many successes in sports. I figured that excellence in yeshiva would be similar. I’ll be a Torah champion, is what I thought.

I quickly discovered that Chabad yeshivos run according to a strict regimen. I put my suitcase down in my new bedroom in the dormitory and immediately joined the learning. The next day, we got up at 6:30 to go to the mikva and then had a Chassidus shiur, Shacharis, breakfast, a Gemara shiur, review of the Gemara with a chavrusa, Mincha, lunch, learning Gemara with a chavrusa, Shulchan Aruch, a Tanya shiur, Maariv, supper, Chassidus with a chavrusa, learning of sichos, bedtime Shema, and the lights were turned out at 11:00.

The day’s schedule was packed and very tough and my life wasn’t easy in any case since English is my mother tongue and I could read a little in Hebrew, but Aramaic? I was encountering this language for the first time in my life.

One day, I called home to talk to my parents in America. I told my father that the Gemara is written in Aramaic. For a moment he was silent.

“Are there countries where they speak Aramaic today?” he asked.

“Not that I know of,” I said.

“Then why are you learning Aramaic texts?” he asked.

“If only I knew,” I joked. “It seems this is how religious Jews love to learn.”

I also knew about Yiddish because my grandparents, who lived in Brooklyn, spoke Yiddish. Unfortunately, I didn’t know a word of Yiddish.

In my first days in yeshiva I encountered Rashi letters which is a certain way of writing the alef-beis letters. Some of the Rashi letters are very similar to others and it was hard to read, especially for a new Hebrew speaker.

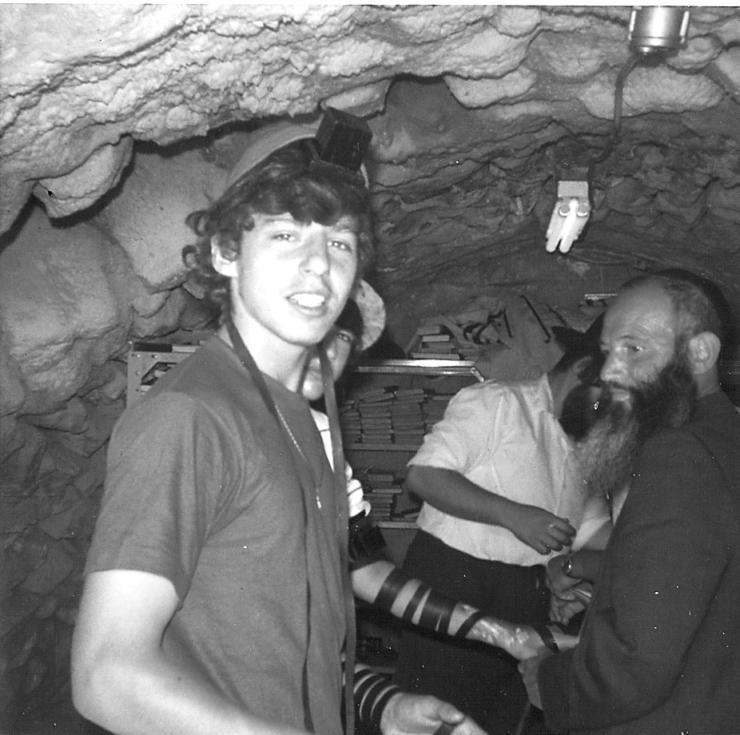

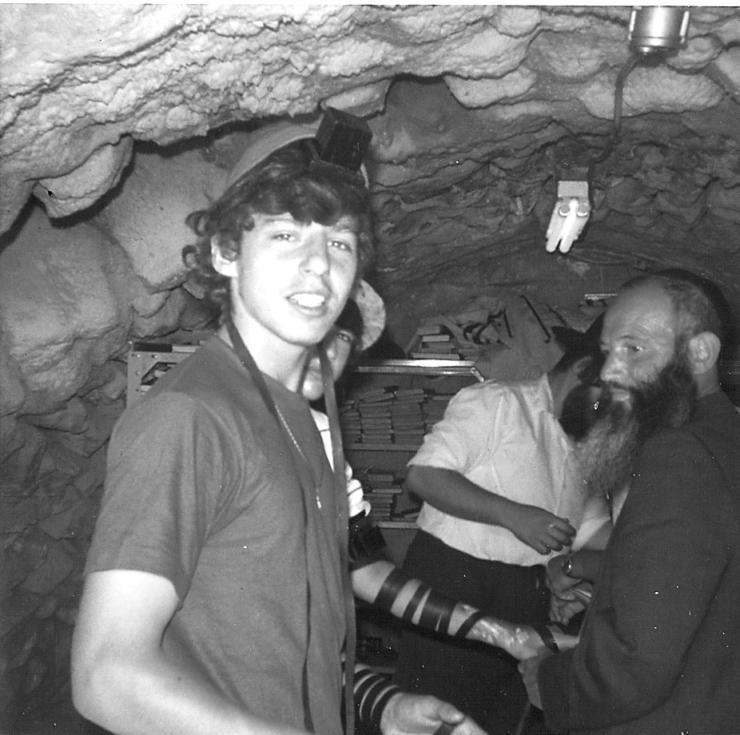

1974. Putting on tefillin for the first time at the Kosel at the Chabad stand.

I asked the rabbi, “What bothered Rashi about the usual letters that he had to invent his own way of writing?” The rabbi laughed, although I hadn’t meant to be funny. I was chagrined to discover that the hours from early morning until late at night were devoted to studying only these texts. I had to translate a lot of them into English.

The main challenge was comprehension. Being able to read the words is not the final challenge. All the concepts were completely new to me.

“Gud asik mechitzasa” (a barrier that does not reach the necessary height is considered as if it does). “Arba’a avos nezikin,” “mu’ad, “tam,” and as for the simple word found in the mishna, “hamav’eh,” there is a dispute as to what it means. One minute. These are Amoraim? Until when were the Tannaim? The Geonim were before or after them?

I was soon all mixed up. Fortunately, the Gemara and halacha include concepts that I was never exposed to but I could imagine them. I had seen a sukka, so I could understand that above twenty amos it turns from a temporary dwelling into a permanent dwelling and is no longer considered a sukka. Everyone can also picture if there is a common area and those living there want to divide it between them, they will all have to share in building a separating wall.

The biggest problem was when I opened a maamar Chassidus. How could I imagine what “machshava keduma d’AK” is? What “malchus d’atzilus ha’mislabeshes b’malchus d’beriah” is? What “ratzon d’ana emloch” is? And in general, why it has to depart until the shofar is blown? That was a serious conundrum.

To my good fortune, I was happy to discover that the Rebbe’s sichos are in Yiddish. Aha, I thought, my grandmother’s language! But in the end, it’s not pleasant to admit this, I wasn’t able to understand the sichos.

Beyond the challenges of language and comprehension, yeshiva life provided another challenging demand in that I had no time for physical activity. Over the years, I was used to engaging in sports regularly. Now, all my energy was channeled just into learning. The mashpiim said explicitly, “The main goal of Tomchei Tmimim is not just learning; it is incumbent on them [the students] also to meditate on Chassidus before davening, to internalize and change the essence of the animal soul of each one…”

Half a year passed in this way, with my psyche in a state of utter confusion.

A NEW CHALLENGE

One night, at the beginning of Chassidus seder, R’ Moishke Naparstek called me over for a talk as I was learning. We were in the zal. R’ Moishke stood, as usual, in the entrance, supervising the hundreds of bachurim and indicated with a head motion that I go over to him.

“How are you?” he asked.

“Fine, thank G-d,” I said. I didn’t say the truth.

“How’s the learning going?”

I began to stammer. I didn’t want to disturb him and I was embarrassed to admit the truth, but I felt he would understand and I decided to be candid.

“It’s hard for me. I’m constantly tense. I don’t understand all the new languages, I’m not internalizing the material and I’m not meeting the requirements.” I could have gone on for hours but he had heard enough.

“Have you started reviewing Tanya?” he asked. He realized I didn’t understand what he meant and so he clarified, “By heart. Chabad reviews Tanya by heart.”

“I never heard of that,” I admitted.

“The letters of Tanya are holy,” he said. “You need to engrave them in your head.”

“Where do I begin?”

“From the first line, ‘Likutei Amarim …’”

I sat in a chair near the window of the zal that faced the Beis Menachem shul. My face to the wall, I held a small Tanya. Since R’ Moishke said there wasn’t a particular method, there was no need to understand it, and that the goal was only to engrave the letters, I did it.

I examined the first letter, “lamed.” I first concentrated on the upper half and tried to engrave it in my heart. I verbalized the letter “lamed” with enormous concentration, like someone trying to remember a very important thing, and then I let it go … Time after time, I repeated this, for an hour, until I felt that the upper half of the letter “lamed” was set in my mind. Then I moved on to the lower half of the letter.

After a long time, when I felt that the letter was alive within me, I stopped. I was in heaven. They had finally given me an assignment I could do. As I mentioned, before I became a baal teshuva, I had been trained in an extremely tough physical discipline and was used to doing repetitions of this type until my soul gave out in order to sharpen the movement of the hand or foot, so this too, came naturally to me.

I went to the dorm, recited the bedtime Shema, pulled up the covers and continued reviewing the letter. In the morning, after Modeh Ani, I continued to review the “lamed.” I repeated it in my mind even when I went to the mikva and also when I entered the zal with the other bachurim.

In the same chair and with the same method, I began working on the letter “kuf” for a long time. Slowly, slowly, letter by letter, three hours a day, every day, I reviewed.

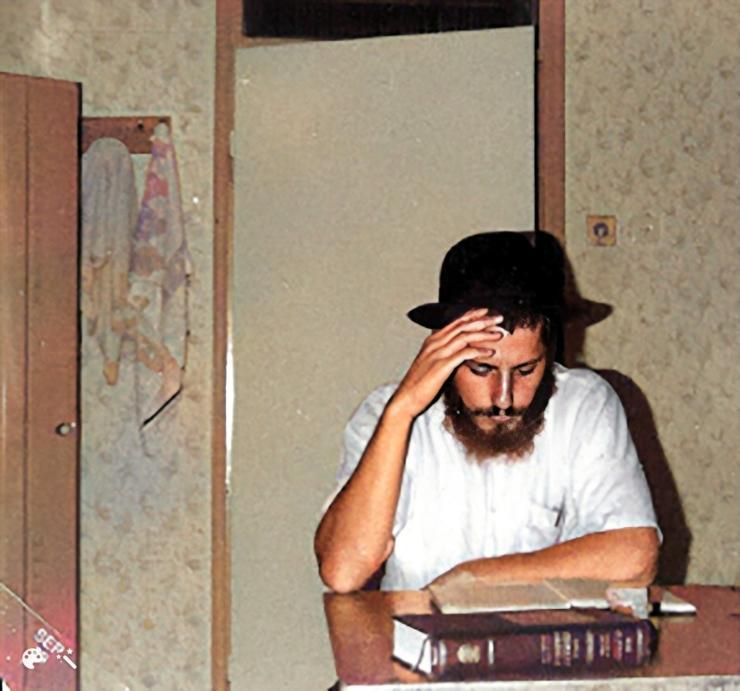

Rabbi Fishel Jacobs learning Torah.

A TEST WITH MEANING

Four months later, one night at Chassidus seder, I went over to R’ Moishke.

“Can I say a chapter of Tanya for you?” I asked.

“Gladly.”

I faced him at his usual spot at the entrance and gave him my personal Tanya. He held it open in front of him even though he knew the chapters by heart.

“Likutei Amarim, Sefer shel Beinonim, perek alef. Tanya b’sof perek kama d’Nidda, mashbi’im oso: tehi tzaddik v’al tehi rasha …” I connected the letters into words and the words into sentences. He smiled with nachas.

“Can you sign to it?” I asked.

He signed in the back cover: “On 10 Shevat 5739, he was tested on chapter one of Tanya by heart and knew it excellently.”

He returned the sefer to me. “What’s next?” I asked.

“Perek beis, of course.”

Two months later, I went over to R’ Moishke again.

“Can I say a chapter of Tanya for you?” I asked again. I was tested and knew it. He wrote down the date and signed.

Although I invested myself into the other studies, the only thing I was really successful at was engraving the letters of Tanya. I devoted time every day to review the earlier chapters too.

IN YECHIDUS WITH THE REBBE

I returned to America for the Pesach break of 5741. I wanted to visit 770 and spend the Seder with my parents who lived in Vermont. At that time, the end of Nissan was when guests to Crown Heights were able to have yechidus with the Rebbe before they left. The designated time for this was at night until dawn.

Before I went, I put a tape recorder into my mother’s handbag, since she was coming with me. I knew that every word the Rebbe said was significant.

Men, women and children, Chassidim, religious people and everyday Jews waited in and outside 770. Those who were going in for yechidus stood and recited Tehillim. At two in the morning it was our turn. The Rebbe’s secretary, Rabbi Groner z’l, brought us in.

The Rebbe told us to sit. The atmosphere in the room was very pleasant. The Rebbe spoke to us in English with his accent that had a cadence like Lashon Kodesh. He asked a few questions about our family and blessed my mother with parnassa, nachas from everyone in the family, and health. He blessed me that I advance in Torah and mitzvos with joy and inspiration and that I should be a Chassid, yerei shomayim, and a lamdan. That was meant to be the end but my mother brought up something that was important to her, a shidduch for me.

The Rebbe smiled. “The main thing is to receive real nachas and to receive it with good health and good parnassa.”

My mother added, “And to find a nice girl for him, a good shidduch.”

“Is he ready now or is he in the middle of his studies?” asked the Rebbe, and he turned to me, “Are you ready for a shidduch?”

My mother nodded eagerly and I said, “I discussed this with my teachers in yeshiva.”

“What was their opinion?” asked the Rebbe.

“That it was advisable after Pesach.”

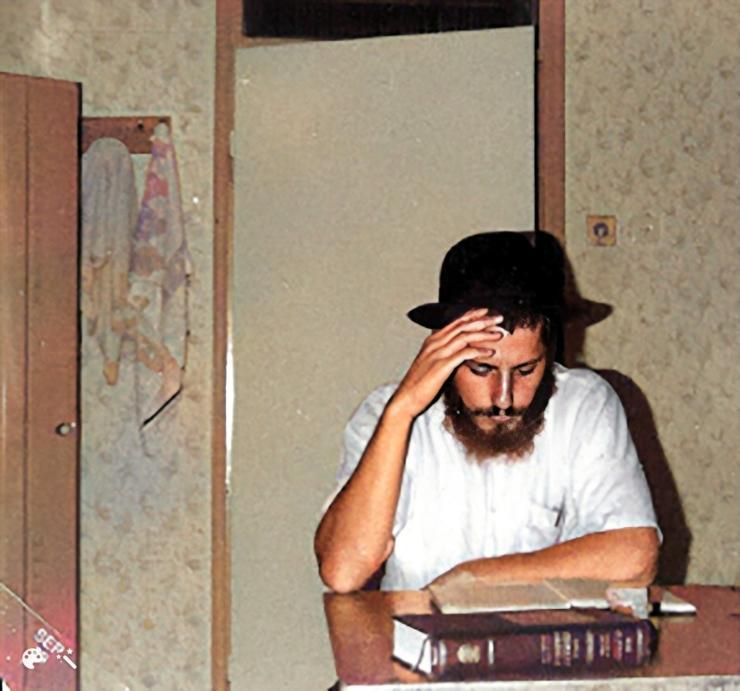

Rabbi Fishel Jacobs receiving kos shel bracha from the Rebbe.

“It is a week after Pesach. How old are you?”

“Twenty-five.”

“Then it’s an appropriate time to be a chassan and then to establish a family. You are staying here?”

I said, “I wrote to the Rebbe shlita about this. I asked his opinion. I am learning in Kfar Chabad and I entered shiur alef.”

“Did you get semicha?”

“I spoke with Rabbi D who said, ‘Generally, a year after the wedding is a good idea.’”

The Rebbe said, “In order to be a year after marrying, you need to get married first! Did you start learning for semicha?”

“No.”

“Don’t you intend on starting?”

I left the yechidus with two conclusions. One, I needed a shidduch and two, the Rebbe was telling me to be a rav myself and to get semicha. The next day I returned to Eretz Yisrael. I told R’ Moishke about semicha and he said it was clear and I should start immediately.

ANOTHER CHALLENGE: BEING A RAV

I married my wife Miriam in Elul 5741, four months after the yechidus. I started learning in kollel which was at first in the yeshiva gedola building and then moved to the 770 replica in Kfar Chabad.

It was years later that I realized that Tanya had changed something inside me.

When I returned to Eretz Yisrael, I was in the shiur for semicha given by Rabbi Tevardovitz. We learned hilchos melicha as per the course of the yeshiva’s tests for semicha. Although the learning was very hard, I managed them successfully.

To be honest, I felt I had to adopt the “by heart” approach here too. My Hebrew was still not perfect and there were many views to remember: the Mechaber, the Rema, the Shach, the Taz, the Be’er Heiteiv. I knew that the test would be given by a big rabbi, under time pressure, in the presence of everyone in the class. So to prevent forgetting, I reviewed everything the Mechaber said, word by word, and a one sentence summary of the Rema by heart, along with the key words in the Shach and the Taz.

A year and a half went by and in this way I reviewed all the halachos of basar b’chalav, taaruvos, Shabbos and eiruvin.

In 5743 I was give semicha by the yeshiva.

I still yearned to learn Torah and with the consent of my wife I wrote to the Rebbe that I wanted to study and be tested for semicha by the Rabbanut. In those days, doing this was very uncommon.

The Rebbe gave his approval and I was tested in 5746. I finished the rabbinic legal counsel course in 5747. All that time, I was particular to review Tanya. Every year, the Rebbe approved my continuing to learn, until 5752. All together, I spent thirteen years in yeshiva and kollel. That year, I was selected to serve as a prison rabbi/chaplain, a position that I held until 5765.

In the years that followed, I wrote many sefarim that earned the approbation of gedolei ha’rabbanim including sefarim on tahara, hilchos Shabbos, and a book for children based on the mashal of the “small city” in Tanya.

PLOWING AND WORK

Looking back, what did I experience?

Today, in 5782, at the age of 66, I sometimes look back to when I started out, nearly fifty years ago. As my teacher told me, I began, with kabbolas ol, to engrave the letters of Tanya by heart. For three years, my only achievement in Torah was engraving the letters of Tanya.

The Rebbe saw things differently. He saw that the letters of Tanya changed something in me and had given me strength. Hard earth is not suitable for the planting of seeds to take and certainly not to produce a bountiful harvest. But if you plow, soften the earth, moisten and fertilize it, the earth will yield fruits.

When I arrived at yeshiva I was not a vessel fit to receive. After I enabled the holy letters of Tanya to live within me, with time, the earth softened and became able to absorb the letters of Torah. Certainly, the Tanya itself is empowering but I think that the main thing was preparing the ground through the constant review.

Without a doubt, all my Torah attainments, in writing sefarim and in the rabbinic positions I’ve filled, would not have been possible without the impact the letters of Tanya had on me; continuous daily constant review for years, until this very day.

THE GRANDDAUGHTER DID NOT FREEZE IN THE SNOW

I’d like to end with a story that is very close to my heart, a story told by R’ Mendel Futerfas, the main mashpia during my time in yeshiva. I often remember this story and it gives me the strength to review and engrave the letters of Tanya. I’ll quote it as it is engraved in my mind.

One night when R’ Mendel was in Siberia, he came upon the house of an old man. It was a frigid winter and the grandpa was waiting for his granddaughter to come to his house. So they waited together.

Some of Rabbi Fishel Jacobs’ books and sefarim. He credits all of it to Tanya.

A few hours later, the old man’s dog ran and barked near the door. Since they didn’t think it meant anything, the two of them ignored this. Some minutes later, the dog ran and barked again and again, they ignored it. When this happened a third time, they realized something was amiss. The two left the house and ran after the dog who led them deep into the forest. There, in the dark and cold, they discovered the granddaughter, frozen in the snow. They quickly picked her up and brought her to the house where they warmed her, gave her tea, and saved her life.

That’s the story. What’s the nimshal?

The night and the cold of the Siberian winter symbolize our world, the body and gashmiyus. The grandfather is the Rebbe, holiness, perhaps G-d Himself, and the granddaughter is man’s soul. Who is the one that calls for help? The letters of Tanya said by heart.

Those who are in a Chabad educational setting are in a hothouse so they don’t necessarily feel the need to adopt methods of warming themselves up. Although most of my life I have been able to write or work in some framework of kedusha, that doesn’t mean that the Chassidic warmth automatically remains within me. Still, despite the cold and darkness of night that prevail in the world, my feeling is that reviewing the letters of Tanya allows the inner animal to bark and call for help. The granddaughter is still waiting to be rescued and she has a chance to survive in the face of the Siberian winter.

For these reasons, I saw fit to write my story, mainly to encourage and strengthen readers to regularly engrave and review the letters of Tanya. Each of us wants the promised Geula as fast as possible and thinks of things to do hasten it. They are all fine, but there is serious weight to the engraving and reviewing the letters of Tanya.

*

The magazine can be obtained in stores around Crown Heights. To purchase a subscription, please go to: bmoshiach.org

200

Join ChabadInfo's News Roundup and alerts for the HOTTEST Chabad news and updates!