Reb Levik To The NKVD Interrogators: “I Bribed President Kalinin”

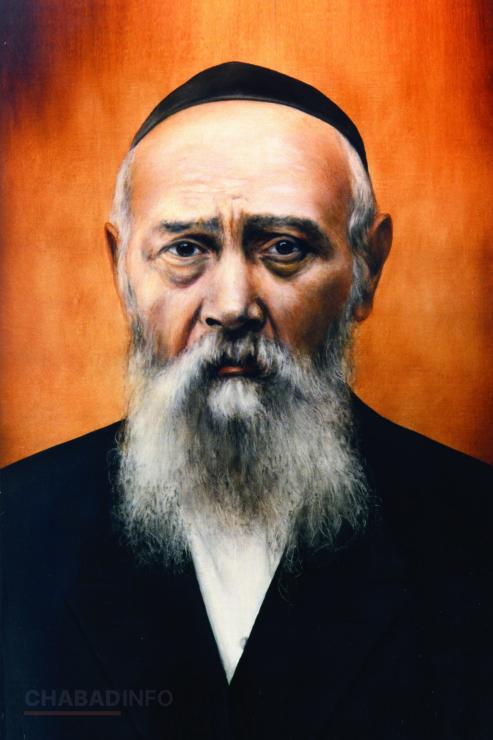

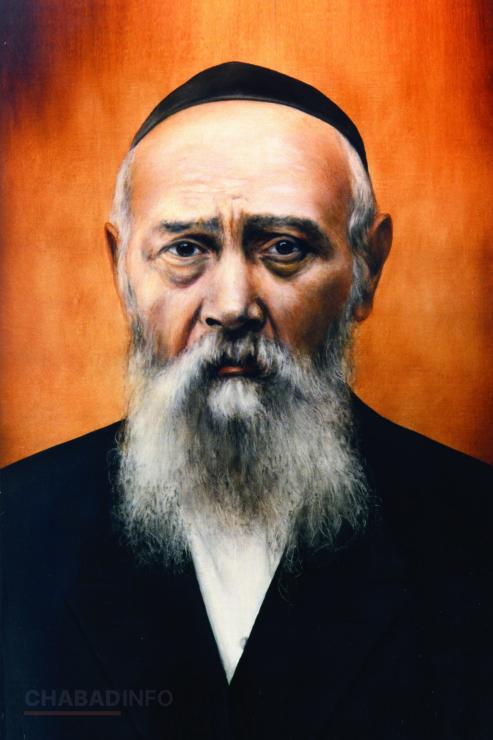

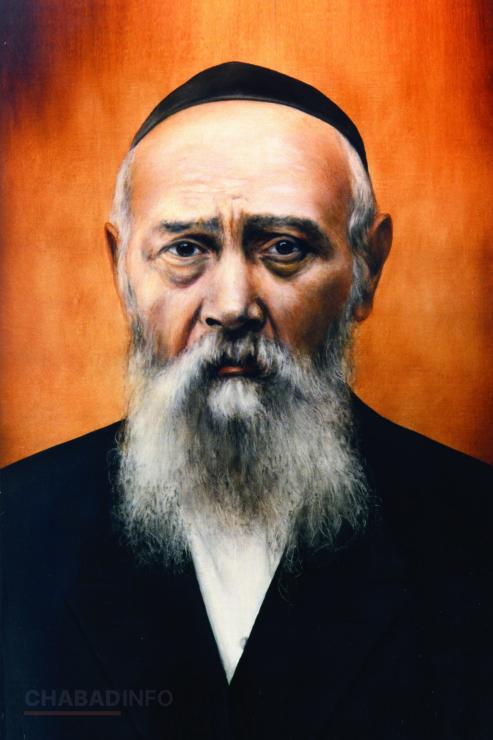

Snippets from Rebbetzin Chana’s diaries, describing heroic scenes from the life of her husband, Harav HaGaon HaChassid HaMekubal R’ Levi Yitzchok Schneerson • Presented in honor of his 79th Yom Ha’ilula on Chof Menachem Av• By Beis Moshiach Magazine • Full Article

By Shneur Zalman Berger • Beis Moshiach

Snippets from Rebbetzin Chana’s diaries, describing heroic scenes from the life of her husband Harav HaGaon HaChassid HaMekubal R’ Levi Yitzchok Schneerson.

Eight days ago was the fourth anniversary of my husband’s passing. “What a misfortune is the loss of those who have left us and left none like them!”

I would like to continue recording my memoirs of that period, and will attempt to do so.

Time passed, month by month, with the established routine. My husband had been charged with certain crimes – propaganda against the government, for which purpose it was claimed that he maintained contact with foreign embassies, rendering him an “enemy of the people,” which was punishable by death. But since they were unable to prove this by any of the means they employed, he was arrested as a “danger to society.”

Consequently, he wasn’t allowed to live in any community—mainly of Jews, of course—so that he would be unable to utilize his spiritual powers to influence others.

Accordingly, his correspondence was strictly censored. Letters between us always took a long time, which was very upsetting. He was prohibited from corresponding at all with anyone else, and people were afraid even to send him regards through my letters.

“Make sure Yud Tes Kislev is Happy”

At the end of the month of Cheshvan, I received a letter from him. He had hurried to send it out as early as possible for fear that it might otherwise not arrive in time. In the letter, he asked that I should see to it that the mood in our home on the 19th of Kislev should be a Yom Tov one, with good food etc. He even listed all minor details necessary for preparing the celebration, particulars he would usually not be involved with while at home. He also directed me to cast all negative feelings out of my mind, and to ensure that the day be a real Yom Tov.

Declaration of faith in the stronghold of heresy

Before Pesach of that year, the government conducted a census of the entire population. One of the questions was, “Are you a believer in G-d?” and some believers were fearful to identify themselves as such. So my husband ascended the bimah in the synagogue on Shabbos, when a large crowd was assembled, and declared: “Failing to respond correctly is true heresy; no Jew may do so!”

His words had such a remarkable impact, that one individual with a position in a government office whose wife had already written on the form that he was a non-believer, went to the statistics office and asked for the erroneous information to be corrected—that he was, in fact, a believer. Very pleased that he had mustered the courage to do this, the fellow came to thank the Rav for having influenced him so.

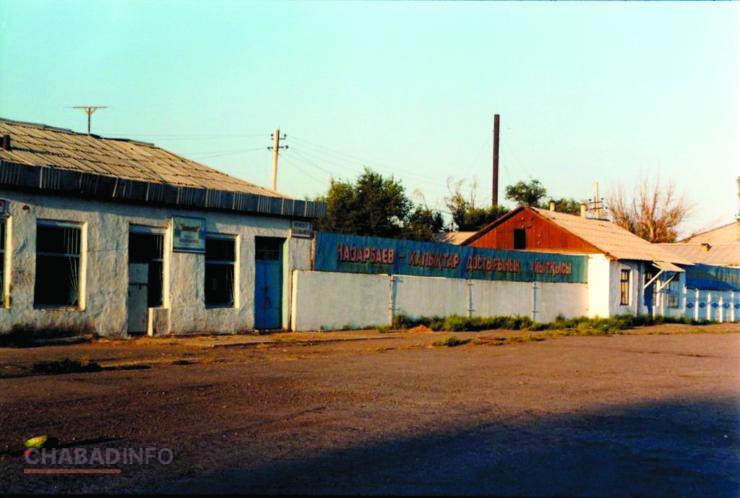

Post Office in Chili where Reb Levi Yitzchok Was Exiled

“When I visited Kalinin, I bribed him”

In the course of his interrogations—they were usually held around 3-4 a.m.—he was asked: “How were you able to carry out such a major (matza baking) operation, and for religious purpose, no less, during a year when there was a shortage of flour and food in general?!”

My husband replied simply: “When I visited Kalinin, I bribed him, so he gave me a permit.” The interrogator, may his name be erased, was speechless.

The second thing they asked concerned his public address about the census question on faith. It was clear that everything he said in the synagogue had been relayed to them, word-for-word. They had, evidently, planted an agent to watch my husband’s behavior, and to observe his influence over the people. We later learned that one of the congregants had been the informer.

My husband replied that the Soviet regime achieves all its objectives only through truth. So for a Jew to openly misrepresent his true belief, out of fear for losing his livelihood etc., would be untruthful! He dutifully insisted that no one deceive the census-takers.

Oh, how wisely and cleverly he deflected their questioning! His responses put an end to both of these lines of inquiry.

“I will never forget Levik Zalmanovitch”

25 Shevat, 5708 (1948)

During this entire time I was not given the opportunity to see my husband. I did, however, receive written regards. This was in the form of a letter that arrived from Nagayeva Bay, from a fellow who spent Pesach in a cell in Kiev together with my husband. My husband later told me that he was a non-Jewish professor who was on the verge of committing suicide, and my husband dragged him away from a prepared noose.

This information was very welcome to me. In reporting on my husband’s health, he wrote that he will never forget Levik Zalmanovitch—his sharp mind and his broad knowledge. He reported that they were four people in one cell, and that the other three survived only due to my husband’s encouragement not to allow all the torment to demoralize them.

The man was also impressed by my husband’s fortitude. Like the other prisoners, my husband was ordered to remove his beard. Amongst the prisoners were rabbis and elderly religious Jews who tried to prevent their beards from being removed, but to no avail—they were forcibly shaven. But when “S’s” turn came, he stated defiantly: “You will not remove my beard!” Frightened, they relented and let the matter be.

Indeed, as I later observed for myself, he was the only prisoner with a beard. Naturally, many pious Jews were envious of him for this.

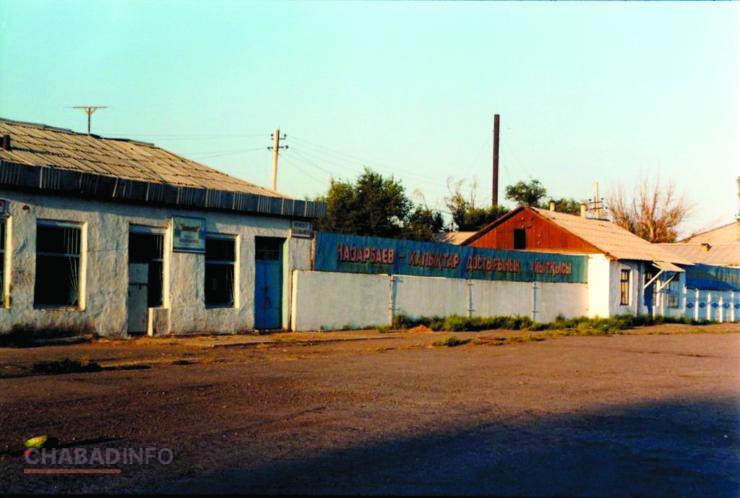

Portrait of Reb Levi Yitzchok – By R’ Elozor Kalman Tiefenbrun

To deliver a discourse on Beis Nissan

2 Nissan 5708—1948

I have not written for so long… For some reason I am finding it difficult.

Today, 2 Nissan, reminded me of the first time that I traveled to my husband’s place of exile for Pesach. The year was 1940. Physically, my husband was not well on this day. It was only two months after the grueling etap to exile, and the living conditions there were worse than I had imagined they would be. Yet on this day, he forgot about everything.

“Today is Beis Nissan,” he stated. “It would be proper to deliver a Chasidic discourse—but there aren’t too many listeners. I would like to pen a dissertation but, alas, there is no paper on which to write. Contemplation will need to suffice—may G-d grant me the strength to think.”

— A week before Pesach I traveled to the city of Kzyl-Orda and brought back two notebooks, powder with which to prepare ink, and a small bottle to serve as an inkwell. This gave my husband indescribable joy, and he immediately began writing. He took to the writing with more enthusiasm than to eating the bread that I had brought for him after such a long and arduous hunger period. —

My husband sat for a while immersed in his thoughts, and then began speaking about the Rebbe, Rabbi Shalom DovBer, completely oblivious to his surroundings and his state of affairs.

The heat was then so intense that it was impossible to sit fully dressed. I recall how in the evening, I brought my husband a fresh change of clothes, and at around 10:00 in the morning the shirt was already covered in black specks… This was caused by fleas, which soiled the shirt over the course of the night. It was simply intolerable. After a while, we managed to find rooming with less fleas.

When my husband spoke, he would always glance at the stains on his shirt, and would transport himself to a completely different world. He absolutely refused to allow take these difficulties to heart.

The Two Lost Pails

On my trip to Chili, I had brought two new pails [for Pesach use], which I had finally managed to buy after standing in line for an entire day. During the journey, however, they had disappeared, as could be expected. I sent telegrams to Moscow and Yekaterinoslav about the loss, but they could not be found. The railroad authority promised to compensate me for this with seven rubles, but to collect I would need to travel to the main office in Tashkent. As usual, this didn’t resolve the problem, and the pails were not found.

Without Pesach utensils, my husband was unequivocal that he would not eat during the entire festival. I resolved to do something about it.

A four-hour journey from us lived a group of Jewish deportees from Kiev in close proximity to each other. Evidently, it was a relatively well-organized community. Among them were a Rabbi, a shochet, and a communal leader named Kalyakov, who had been among the wealthy Jews of Kiev. I traveled there in an effort to find a solution for my serious problem.

During the two days I spent there, I had a tin-plate pail made for me from new materials. Then I ordered meat and fish, requesting that they be delivered the day before Pesach.

Best of all, after I arrived at the train-station, someone gave me more than a kilo of black bread. In retrospect, I don’t understand how we were able to eat that kind of bread. (I should add, however, that the black bread never harmed us. In fact, after falling ill with dysentery later that summer, I recovered by eating black bread.)

I was filled with inestimable joy at these successes; especially by the new tin pail, which sparkled!

Meanwhile, life went on.

I even invited a guest for Pesach. The dishes I had brought from home were still clean. We put together a makeshift table from some boards, over which I spread a white tablecloth. The Kazakh who delivered the chicken and fish on the day before Yom Tov couldn’t stop talking about the “wealth” he saw in our home! Parenthetically, in the course of his four-hour trip, the chicken and fish spoiled from the heat, and became too dangerous to eat.

Thus the three of us sat down to conduct the Pesach Seder.

Outside our windows stood a group of young gentiles who mocked us, imitating what they referred to as our “wailing.” Inside, however, we loudly and wholeheartedly chanted [the words of Kiddush] “the Season of Our Freedom… You have given us Your holy Festivals, in joy and gladness, as a heritage.” These words felt so real, as well; considering that my husband had spent the previous Pesach in prison, this year was certainly an improvement.

We continued our celebration until 2:00 a.m., when our guest returned home to sleep. He had a long walk through fields to get there.

“The Rav is a Descendant of a Revolutionary, and he’s doing the same”

[Back in Dnieperpetrovsk,] beginning after midday on Yom Kippur, my husband would diplomatically arrange the length of time the remaining services would take so that they should not end too early, for that would enable the congregants to leave for home and break their fast before it was over. Among the congregants were various types [from more observant to less so, and many wanted to break their fast as early as possible]. Other shuls in town finished much earlier, and to ensure that the same shouldn’t happen here, my husband arranged with the chazzan to stretch out the previous prayer services so that no time was left for singing during the Ne’ilah service.

One of the congregants, a craftsman who considered himself—and was so considered by others—a Torah scholar, became so incensed that my husband was keeping the congregation later than at other shuls, that he spoke out angrily against him. His audacity was somewhat mitigated by the fact that his outburst took place not at the front, eastern end of the shul [where the Rav sat and the chazzan led the prayers], but near the exit. He pointed out that the Rav was a descendant of a revolutionary against the government, who was imprisoned for sowing divisiveness, and now, like his ancestor, the Rav was doing the same!

All this was a great strain upon my husband. Even the finer congregants were unhappy with his extending the length of the prayers, although they kept it to themselves. The more common elements, however, expressed their dissatisfaction openly. Yet my husband was truly gratified by what he was doing, although it was something he had to enforce, because—as he always said—he had accomplished that Jews should not do what was forbidden [breaking their fast when it was still Yom Kippur].

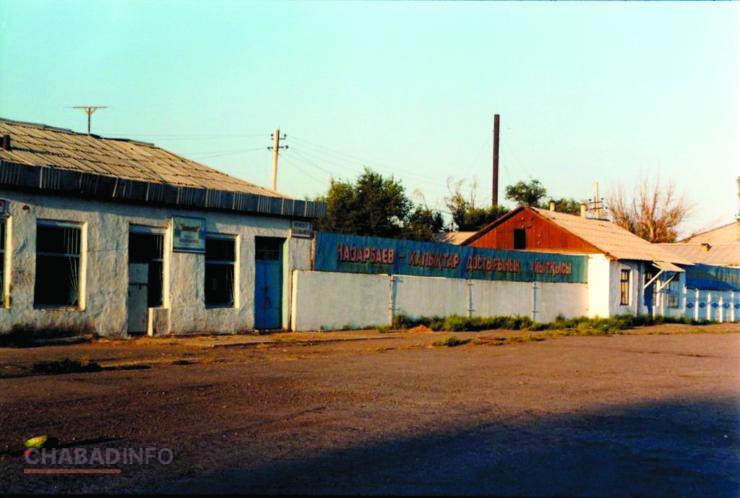

Typical Home in Chili

A Farbrengen with Dancing like Simchas Torah

When my husband would return home after Yom Kippur, he couldn’t easily settle back into the everyday mundane existence. After coming home quite late in the evening, he drank only a glass of tea. Then he remained sitting, still garbed in his kittel and the gartel of his great-great-grandfather, the Tzemach Tzedek, to lead a farbrengen until two or three o’clock in the morning.

This was his regular custom on the evening after Yom Kippur, both when Jewish life had been less constricted and later when Judaism could be practiced almost solely within the confines of one’s own home.

Some of our friends were aware of my husband’s custom, and they would eat a quick evening meal with their families before coming to our home. My husband would deliver a Chasidic discourse on subjects connected with the Yom Kippur prayers. In later years he spoke about the great qualities of Jews, their self-sacrifice to observe Judaism, and how they expressed their love towards other Jews in that difficult era.

Ten or fifteen people always attended this farbrengen, which included dancing as enthusiastic as on Simchas Torah.

The Rav’s final Tishrei

In Russia, during the month of Tishrei, even non-observant Jews become religiously oriented. Accordingly, people started to visit my husband, recognizing him as a central figure for religious affairs. Each had personal questions and requests. They included Jews from Bessarabia, Poland and many other places. Most were women, because the Soviet occupational army in Bessarabia had deported entire Jewish families and, on their journey into exile, had separated women from their husbands, so now they were asking for help in locating their husbands. Everyone’s heart was utterly broken by their experiences.

An exception was some evacuees from Moscow and similar cities, who were gratified that they had been spared from the danger of the war zone and had even managed to bring some of their possessions—which they immediately traded on the market. But they, too, found the cramped conditions, the primitive state of the homes, and the poor climate very difficult to tolerate.

Many of the younger evacuees found employment in various concerns. But they were regarded with envy and lived in constant state of anxiety.

From all these Jews, a large group assembled for High Holiday prayers. None were qualified to serve as a chazzan, Torah reader, or shofar blower. They were simple Jews, and not Torah observant. We had received a Sefer Torah, and I had brought a shofar from home. Since there was no one else, my husband performed all these functions himself. He performed it all with such deep emotion—“My entire being declares”—for he hadn’t had the benefit of such prayer for five years—the entire congregation in a refined state of spirituality, accompanied by copious weeping; it was absolutely awesome.

The walk from the apartment where the prayers took place to our own room was quite a distance. We had to cross two “valleys,” walking downhill and then uphill. On the evening following Yom Kippur, after the Kiddush Levana prayer, when my husband walked into our room, I could barely recognize him—his face had so changed. But he was very happy at having successfully completed all the High Holiday services.

For the first two days of Sukkos, services could not be held at that apartment. For the final days, however, the rental arrangements were renewed. It is impossible to describe that Simchas Torah’s great joy—real dancing!

Participating in the dancing and singing were Jews who back at home, had never done this. Many declared that spending Yom Tov together with my husband in shul enabled them to forget all their troubles, as they felt only his inspirational effect upon them.

Several participants even held special “Kiddush” celebrations at their quarters, inviting others to partake of food and drink. This didn’t happen in any of the surrounding towns; only in our village, because of my husband’s presence there. People declared that they would never forget him.

Witnessing my husband’s rejoicing, one could think he had never experienced any misfortune. But his face already betrayed his poor health. His spirit, on the other hand, remained quite resolute.

* * *

Beis Moshiach magazine can be obtained in stores around Crown Heights. To purchase a subscription, please go to: bmoshiach.org

Translated from Rebbetzin Chana’s Yiddish Diaries, reprinted from Chabad.org

285

Join ChabadInfo's News Roundup and alerts for the HOTTEST Chabad news and updates!