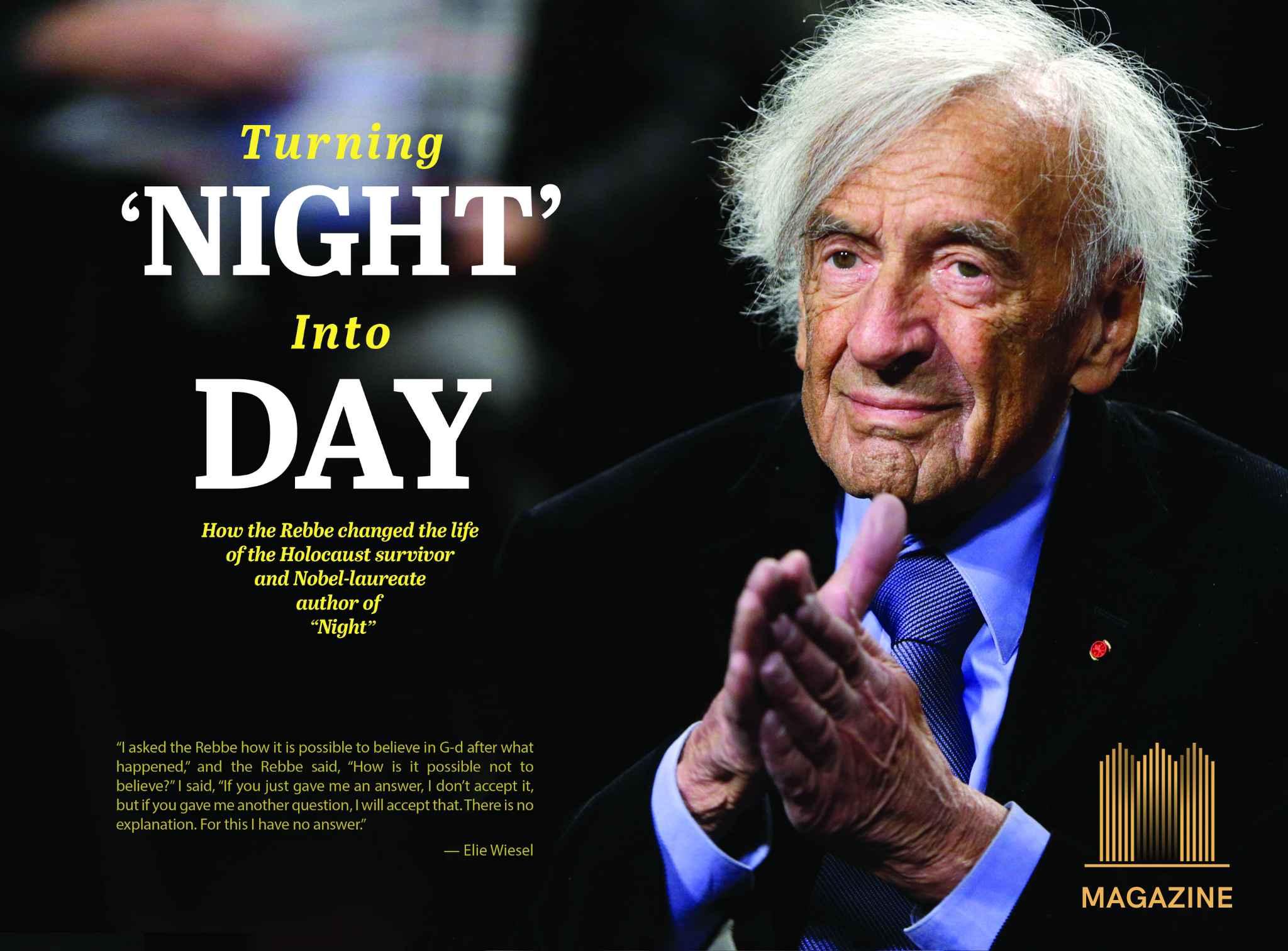

Elie Weisel: Turning Night Into Day

How the Rebbe changed the life of the Holocaust survivor and Noble laureate, author of ‘Night’ Elie Weisel • By Beis Moshiach Magazine • Full Article

By Shneur Zalman Berger, Beis Moshiach Magazine

A Chassid without a beard, a writer (10 million copies sold of Night), Elie Wiesel passed away at the age of 87 in 2016. Wiesel was a journalist, a philosopher, an intellectual and a Holocaust survivor. He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his work on behalf of human rights. He was very involved in educational activities around the world to commemorate the Holocaust.

Wiesel was a big admirer of the Rebbe and was mekushar to him with all his heart and soul. The Rebbe reciprocated his love and encouraged him and worked to lift Wiesel up from the spiritual and material abyss into which he had sunk in the years after the war.

HOLOCAUST SURVIVOR AND NOBEL PRIZE WINNER

More than anything else, Wiesel was known as a Holocaust writer for his many books and articles on the horrors of the war that he personally experienced and that the Jewish people went through.

Wiesel was born on 16 Tishrei 5689/1928 in Sighet, Romania to Vizhnitzer Chassidim who ran a grocery store. He attended the local cheder where he learned limudei kodesh. With the help of his father he acquired a mastery of Lashon HaKodesh in addition to the Yiddish which all the Jews in the town spoke, and German, Romanian and Hungarian, the local languages.

The Germans occupied Sighet and a few months after living with his family in the ghetto, he was sent in Nissan 5704/1944 to Auschwitz. There he did slave labor and suffered immensely. Of his extended family, only he and two sisters survived.

He began working as a journalist after the war. Despite his superlative writing, he wrote nothing about his war experiences. However, a meeting with writer Francois Mauriac changed his perspective on the past and he began writing his bitter memories of his suffering.

He then moved to New York and began writing for a Yiddish newspaper. He also became a writer for the Yediot Acharanot along with his work editing books and activities to memorialize the Holocaust. During the following years he wrote dozens of books and hundreds of articles on the Holocaust and became a dominant figure in Holocaust commemoration. He was very involved in publicizing the plight of Soviet Jewry who were oppressed under communist rule. In his Jews of Silence he wrote his impressions of Soviet Jewry and Lubavitch Chassidim. For his public work he won prestigious prizes.

For many years after the Holocaust, although he was considered a success story, he was unable to free himself from the baggage that plagued him from the terrible years in the death camps. Depression was a part of his everyday life and his psyche was embittered. He even refused to marry and chose to remain alone and lead a solitary life.

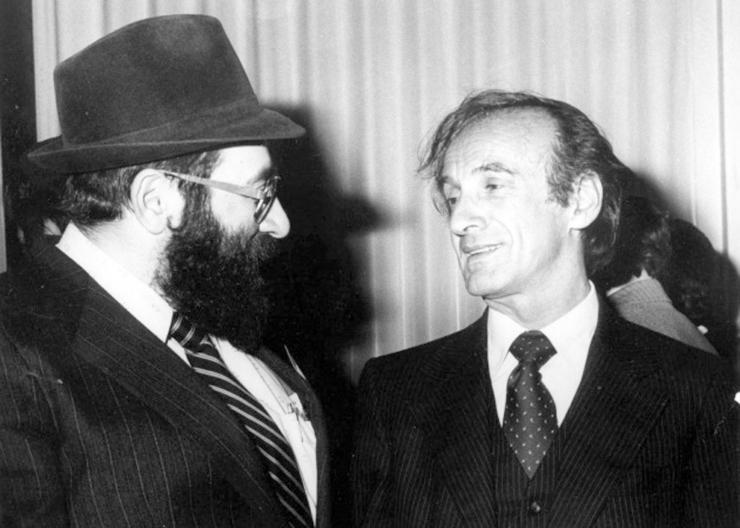

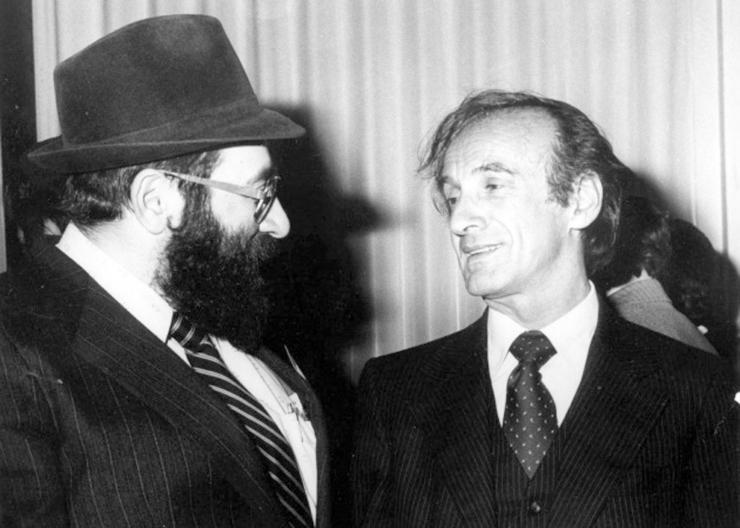

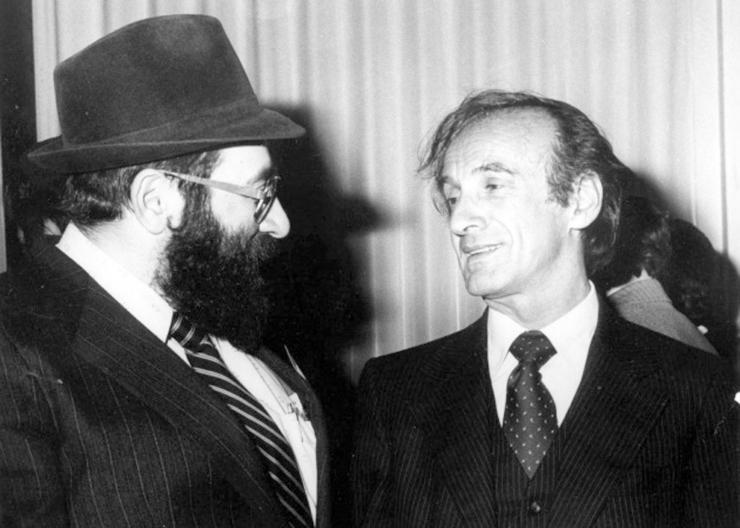

Elie Wiesel with shliach, Rabbi Sholom Dovber Kalmanson (a son and grandson of Holocaust survivors).

MEETING THE REBBE

Rabbi Gershon Ber Jacobson a’h, a Chabad Chassid and editor of the Algemeiner Journal contacted Wiesel in connection with their shared journalism work. He eventually brought Wiesel to the Rebbe. Wiesel, who began attending farbrengens, wrote his impressions which were printed in newspapers. This is a moving description that he wrote for Yediot Acharonot, 11 Nissan 5722, when the Rebbe turned 60:

“It is already a number of years that I have been coming to view the special holiday celebrations of the Lubavitch Chassidim, and they do not lack for such holidays, baruch Hashem. They celebrate the release of the first Rebbe from Czarist prison, the release to freedom of the Previous Rebbe, the yahrtzeit of the father of the current Rebbe; in short, Lubavitch Chassidim love to be joyous and know how to be joyous. This week they celebrated the 60th birthday of the Admor Rebbe Menachem Mendel Schneerson shlita, and whoever did not see this celebration, never saw joy in his life.

“Amid the thousands of Chassidim in the hall in Brooklyn, I stood at some distance from the stage, for hours and hours, without missing even a second of seeing the bearded face of the Rebbe. I never saw such a power-exuding face and such eyes.

“There is power in them that frightens and soothes, that inspires and consoles, and there is a will of steel in them. It seems as if a look from him can bring close the end of time. Contrariwise, there is reflected in them a blazing sadness, such that seems to rebel against itself. For days after I return from there, I walk around under the impression that his eyes accompany me at every step and read each one of my thoughts. Many-many years have passed since I was consumed in the fire of Chassidus. And yet…”

Wiesel spent a great deal of time studying the relationship between the Rebbe and the Chassidim, and the Jewish people. As a (Vizhnitzer) Chassid from home, he knew from up close the deep soul connection between the Rebbe and the Chassidim. “A Rebbe is a man who contains the soul of his Chassidim, who gives them the power to actualize the potential that is latent in them and grants them joy and verve. The Chassidim receive their soul-needs through the connection to the Rebbe. And that is the difference between a Rebbe and a Rav (Torah teacher) – a Rav waits for the questions of his students and when these come to him, he responds. A Rebbe does not wait. He grasps the people, awakens them and grants them inspiration.”

In 5746, he was awarded a Nobel Peace Prize for his work in leading the President’s Commission on the Holocaust which President Carter appointed him to, from 1978 to 1986. He was involved in planning and launching the building of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington DC. In 1993, along with President Clinton, he lit the eternal flame during the dedication ceremony. The year before, he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Over the years, he received numerous prizes and awards for his literary and humanitarian work.

Receiving lekach from the Rebbe

DIVINE MYSTERIES

The special relationship with the Rebbe went up a notch when, in 5725, Wiesel wrote an article in a periodical for Jewish lawyers about Jewish atheists. A letter from the Rebbe appeared on the same page on the topic of interfaith dialogue, and that is how his article reached the Rebbe.

The Rebbe sent him a letter which he began by noting that both of their articles appeared on the same page. The Rebbe wondered why he did not mention the approach of “so it rose in the [Divine] thought” [i.e. that one should not question the Creator regarding what happened in the Holocaust.] The Rebbe noted that our nation experienced massacres and persecutions in previous generations but with the Holocaust it became clear that a person could be a philosopher and poet, a cultured individual, as well as a mass murderer.

The Rebbe concluded that one cannot rely on humanistic culture and on feelings of justice that beat in the hearts of humankind even if those people are possessed of high culture and armed with a university degree or any academic certification.

After the philosophical-religious explanations, the Rebbe concluded that the survivors of this tragedy need to be role models to show that Hitler was not successful and in order to anger Hitler and his associates – and here, the Rebbe appealed directly to Wiesel – he needed to establish a large family, sons, daughters and grandchildren:

“I will permit myself to say in the strongest possible terms that despite how important it is to relate what happened to us to the present generation, and notwithstanding how hard it is to free ourselves of those memories and experiences, in my view our most important mission is to fulfill “Al korchach atah chai,” [you must live] with the emphasis on “atah chai” [you live], i.e. that the liveliness should be apparent.

“In other and clearer words, you must make every effort to tear yourself away this very moment from your memories and enter into a structure of family life, to establish a Jewish home and a Jewish family. This will certainly help bring about the downfall of Hitler in that he did not actualize his desire to destroy an additional Vizhnitzer Chassid.

“On the contrary, you will raise children and grandchildren who are Vizhnitzer Chassidim until the end of time. I don’t mean this as a literary witticism, although I am not distinguishing here between a Chassid of Vizhnitz, Lubavitch or an ordinary Jew who is observant of Torah and mitzvos, but if it could actually be that way – that is certainly good. And just as in the past you experienced difficult things in your life and now you are in America, so too, if you truly want it, you will attain this as well and Hashem will grant you success.

The Rebbe ends the letter by noting that although his letter is long, “but if after Shavuos you will marry k’das Moshe v’Yisrael and with mazal tov, my writing will have been worthwhile and your bother in reading it will have been worthwhile.” (Igros Kodesh vol. 23).

The topic of the Holocaust came up many times with Wiesel sharing his thoughts and pain with the Rebbe as he described in an interview, “I asked the Rebbe how it is possible to believe in G-d after what happened,” and the Rebbe said, “How is it possible not to believe?” I said, “If you just gave me an answer, I don’t accept it, but if you gave me another question, I will accept that. There is no explanation. For this I have no answer.”

Still and all, over time, the Rebbe’s words pierced his heart and he was convinced to marry. On the day of his wedding he received a telegram from the Rebbe with mazal tov greetings and a bouquet of flowers. Wiesel’s wife, Marion Erster, was a partner in her husband’s work and even translated some of his books. They had a son, Elisha Shlomo, named for his father who perished in the Holocaust, and two grandchildren, Eliyahu and Shira who continue the chain as the Rebbe requested.

WITNESS FOR THE REBBE

Wiesel became a true friend of Lubavitch and the Rebbe. He often visited the Rebbe and his admiration for Chabad continued to grow as he became a famous public figure who was accepted into the highest spheres of influence in the world and whose voice became a powerful voice heard around the world and by its leaders.

Over the years, in his speeches and media interviews he expressed his admiration for the Rebbe. This is what he wrote for Haaretz which shows the depth of his relationship with the Rebbe: “When I am unsure about personal issues, I think about what my father would have said; when I am unsure about communal matters, I think about what the Rebbe would say.”

Wiesel appeared at many Chabad events around the world. He spoke with love and admiration for the Lubavitch movement and its leader. When necessary, he knew how to debate those who mocked Lubavitch. As an experienced journalist, he did so outstandingly. For example, when political pundits attacked Shazar when he visited the Rebbe during his presidency, Wiesel responded sharply in an article and asked – if the president of the United States paid a personal visit at the home of an author or some other highly regarded person, would it raise ire too?

Out of all his speeches on behalf of Chabad, the most important speech he delivered for the Rebbe was, without a doubt, his unforgettable testimony in the court case over the sefarim. It was 7 Teves 5746, when he was already a respected world figure who was listened to attentively, that he testified to the judges about what is a Rebbe and why he is the leader of the Jewish people. Years later, when Nathan Lewin, who represented Lubavitch in the court case, spoke about the case, he mentioned that the Chassidim must thank the critical witnesses in the case including Elie Wiesel who successfully conveyed the role of a Rebbe as a national leader of the Jewish people.

* * *

FROM A SPEECH BY ELIE WIESEL

As known, Chabad is Lubavitch and Lubavitch is the Rebbe. Chabad also means carrying through a mission: a mission of Chabad and a mission of the Rebbe, its leader, missions from the Rebbe to his admirers, from follower to follower; from emissary to the mass public.

Chabad also means emissaries: these remarkable young men and women whom the Rebbe sends to the closest and far distant places, wherever Jewish people live, and wherever one has to spread Judaism and rekindle the Jewish spark of faith, hope, and redemption.

I would like to offer them a public expression of gratitude and thanks. Let the world know that even in human deserts, Jewish people are not left alone; let the Jewish and Chassidic world know that in the most abandoned cities and hamlets, in small and even smaller colleges the Chabadniks are there, seeking and reaching out to Jewish students, to affectionately offer them guidance and counseling, to expose them to their “roots” and—quite simply—to warm them up.

This does not mean that they are the only ones. There are also other organizations that do what they can and sometimes even what they should do. There are Hillel Houses, Community Centers, and various educational agencies that dedicate themselves to students, affording them an education in the Jewish spirit. However, Chabad is still different.

I sound like a Chabadnik? In order that no one accuses me of misleading, I usually admit at every Chabad gathering that I am actually not a Chabadnik, but rather a Vizhnitzer follower. I am a Vizhnitzer descendant and will probably remain an admirer of Vizhnitz until the end.

I witnessed this more than once. You arrive in a community somewhere in the South, Midwest, and you meet colleagues and students who speak with great fervor about their relationship with Chabad. If not for the emissaries of Chabad, many young people would have been misled and lured into various cults or drug addiction, etc., G-d forbid.

Thanks to these quiet, modest, but capable emissaries, many young people found an address where to find shelter, where they can meet human beings with warm hearts and talk about their problems. In those places, Chabad emissaries are the only contact for youth, with the Jewish people, and with Judaism.

Seattle and Detroit, Madison and Boston, Amherst, Minneapolis and Chicago—no one has invited them, no one prepared any contacts or apartments for them, and in some cases, no one was even aware of their coming. They just showed up one bright morning and began to seek Jews.

Following the first week, they already have a picture of the situation, what has to be done, where, and how much manpower is needed. The following month they have already organized their own center for the students, educational programs, etc. A year or so later, this small center turns into a huge edifice of activities.

Today we already have, thank G-d, hundreds of large branched-out Chabad centers in the United States of America. They draw the rich and the poor, the religious and the non-committed, the children and their parents. You learn, you pray, you sing, and organize joyful gatherings and rallies.

I wish that other Chassidic movements would envy them and also send emissaries, build schools and educational centers, and would also save Jewish souls—should that be the case our situation would be different.

How come the Chabadniks are the only ones in this field? Can we (or are we allowed to) say that others do not have the same self-sacrifice? G-d forbid. Perhaps it is rooted in the fundamental approach of Chabad to Judaism on the basis of education.

For Chabad, education is a fundamental principle. Second, its dedication is also attributed to the personality of the Rebbe. Every emissary feels that he serves in an army where the Rebbe is its Commander-in-Chief. One goes where the Rebbe asks him to, one fulfills all his requests.

I am enthusiastically moved by the Rebbe’s emissaries. I see them on the battlefield, I see how they educate children, how they speak to estranged people. How can one stand from the side? One must lend a hand. One must respond by saying, Amen.

* * *

L’CHAIM WITH THE REBBE

from All Rivers Run to the Sea by Elie Wiesel, pp.402-4

[At m]y first visit to the [the Lubavitcher Rebbe’s] court…I had informed him at the outset that I was a Chassid of Vizhnitz, not Lubavitch, and that I had no intention of switching allegiance.

“The important thing is to be a Chassid,” he replied. “It matters little whose.”

One year, during Simchas Torah, I visited Lubavitch, as was my custom.

“Welcome,” he said. “It’s nice of a Chassid of Vizhnitz to come and greet us in Lubavitch. But is this how they celebrate Simchas Torah in Vizhnitz?”

“Rebbe,” I said faintly, “we are not in Vizhnitz, but in Lubavitch.”

“Then do as we do in Lubavitch,” he said

“And what do you do in Lubavitch?”

“In Lubavitch we drink and say l’chaim.”

“In Vizhnitz, too.”

“Very well. Then say l’chaim.”

He handed me a glass filled to the brim with vodka.

“Rebbe,” I said, “in Vizhnitz a Chassid does not drink alone.”

“Nor in Lubavitch,” the Rebbe replied. He emptied his glass in one gulp. I followed suit.

“Is one enough in Vizhnitz?” the Rebbe asked.

“In Vizhnitz,” I said bravely, “one is but a drop in the sea.”

“In Lubavitch as well.”

He handed me a second glass and refilled his own. He said l’chaim, I replied l’chaim, and we emptied our glasses. After all, I had to uphold the honor of Vizhnitz. But as I was unaccustomed to drink, I felt my head begin to spin. I was not sure where or who I was, nor why I had come to this place, why I had been drawn into this strange scene. My brain was on fire. “In Lubavitch we do not stop midway,” the Rebbe said. “We continue. And in Vizhnitz?”

“In Vizhnitz, too,” I said, “we go all the way.”

The Rebbe struck a solemn pose. He handed me a third glass and refilled his own. My hand trembled; his did not. “You deserve a bracha,” he said, his face beaming with happiness. “Name it.”

I wasn’t sure what to say. I was, in fact, in a stupor. “Would you like me to bless you so you can begin again?”

Drunk as I was, I appreciated his wisdom. “Yes, Rebbe,” I said. “Give me your bracha.” He blessed me and downed his vodka. I swallowed mine – and passed out.”

*

Beis Moshiach magazine can be obtained in stores around Crown Heights. To purchase a subscription, please go to: bmoshiach.org

276

Join ChabadInfo's News Roundup and alerts for the HOTTEST Chabad news and updates!