Beis Moshiach: “I Became A Baal Teshuva At My Public Library”

The life story of R’ Yosef Barnes: his birth to assimilated parents in Nazi occupied Holland; his battle with the polio disease; discovering his Jewishness at age 10; and the Lubavitcher Bnei Akiva counselor who brought him to the Rebbe who in turn showered the self-made Baal Teshuva with fatherly care and love • By Beis Moshiach Magazine • Full Article

By Mendy Dickstein, Beis Moshiach

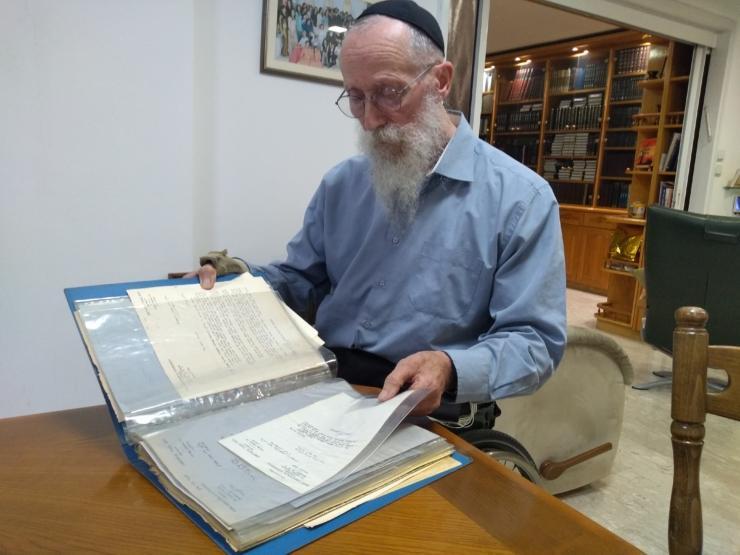

He is one of the older familiar figures in Kfar Chabad. His always smiling countenance and slight accent, that belie his Western European origins, are familiar to every child in the Kfar. Although it is already thirty years since he has been getting around in a wheelchair, his smile and joie de vivre are always apparent.

Meet R’ Yosef Barnes (Berntz), the “Optometrist of the Kfar.” Behind his modest demeanor lies a fascinating life story. His story begins in 5694/1934 when a young man by the name of Werner (Gershon) Berntz was sitting in a Berlin cafe and sipping a hot coffee. Up until that point, he had been a successful person who was well integrated in the enlightened city and had adapted himself to the new winds of progress. By education, Werner was an economist and he worked for a while in a bank, but recently, in the atmosphere of the early days of Nazi rule, he was fired and had no choice but to work in the field of publicity.

Werner was leafing through the daily paper and looking out the window at the busy street. Pictures of the Fuhrer and incendiary quotes from his speeches filled the newspaper, expressing the insanity that was overtaking Germany. Jews were debating whether the enemy really intended on implementing his ideas and proclamations based on the racist theories that he came up with or whether it was a passing phase that would end with words alone. Werner himself was struggling with this weighty question.

He suddenly began to hear snippets of a conversation at a neighboring table. He wasn’t surprised to discover that the people sitting nearby were discussing the fascist nationalist ideas that permeated Germany in those days: Nazism, the Aryan race, and … the “Jewish Problem.” He heard them enumerating many “deficiencies” in the character of a Jew and someone said, “Those Jews are cowards; they have no courage.”

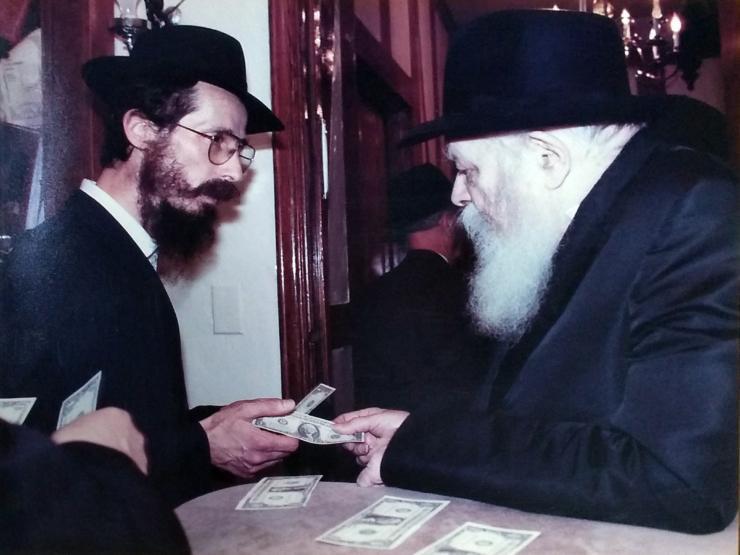

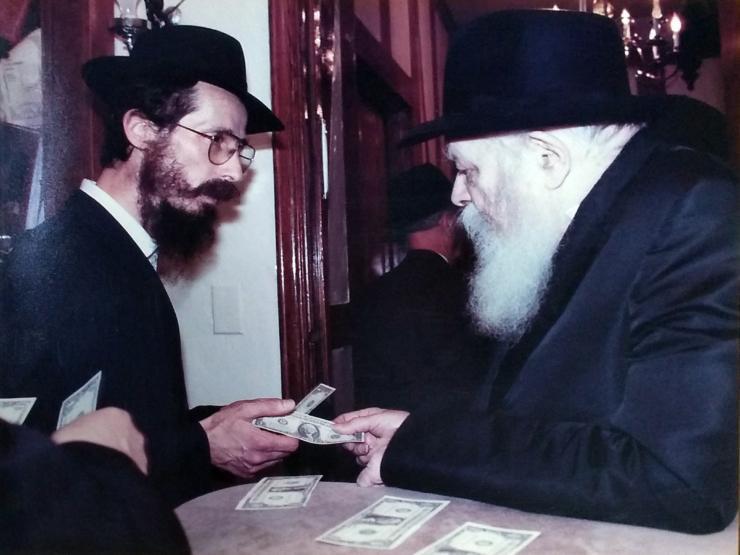

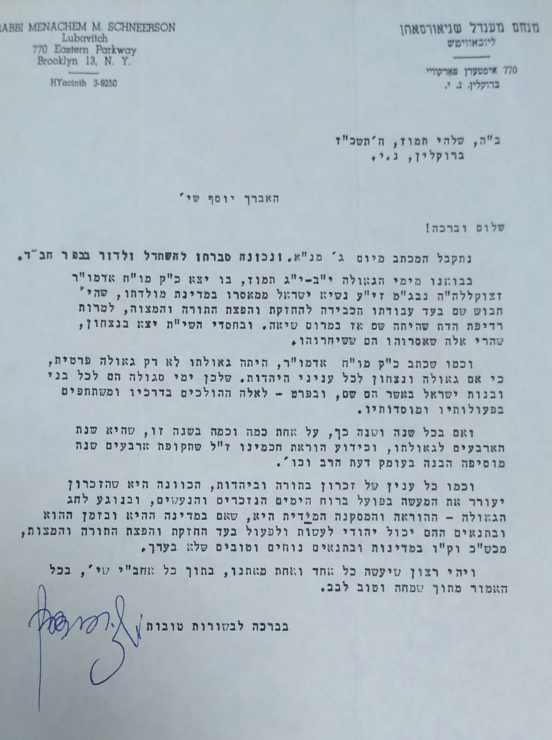

R’ Yosef receiving a dollar from the rebbe

Werner had a difficult time sitting there silently. As a powerful person who had developed his physical skills in the field of boxing at the Jewish club he was determined to prove who, in the coffee house, was a coward and who was brave.

“Perhaps we should go outside and resolve this between us,” he said as he approached them without a shred of fear. The group of youths whose conversation had been interrupted looked at him scornfully. However, they couldn’t ignore the challenge posed by the Jew.

They quickly saw their mistake as Werner Berntz didn’t need more than a minute to make them regret that they had agreed to spar with him. At least one of them was dragged home by his friends and needed medical treatment. The next day, Werner found out that the police were looking for the “Jew who dared to strike a proud German.” On the spur of the moment, Werner decided to flee the country. The question of where to escape to had only one answer; to neighboring Holland.

The country which had been neutral during World War I was attractive to the threatened Jews. Berntz, who knew how difficult it was to obtain a visa to Holland, spared no efforts to flee Germany. He somehow found out about organized tours that traveled back and forth and he was given a temporary transit ticket. “The ticket was for the following day,” said his son, Yosef. “My father wanted to bring a little bit of money with him to Amsterdam. Since he wasn’t allowed to take money out of Germany he came up with a plan. He pretended that he had a contagious disease and taped bandages on his chest and warned the border guards not to remove them for fear of contagion and that is how he crossed the border with his money.”

Was he safe? For the time being, it seemed so. He married Elaine Sofia a Jewish woman from Hamburg who had also fled to Amsterdam together with her two brothers. Two sisters emigrated to England. The couple had a daughter in 1938 and four years later a son, Yosef.

Big changes were taking place in Holland. The Germans did not honor the country’s neutrality and in May of 1940 they bombed the port city Rotterdam. It didn’t take them long to conquer the country. The lives of 110,000 Dutch Jews became more difficult from day to day.

At the beginning of 5741 (fall 1940), a significant change took place for the worse. Jewish schools were segregated from the general school system; higher education was off-limits to Jews. Germans announced that from then on all Jewish stores would be run by them and they confiscated the money owned by Jews that were in the banks. They also ordered Jews to bring their jewels and valuables to collection points, and Jews were later forced to wear yellow stars.

SHE WOULDN’T LEAVE HER FAMILY

The deportation of Dutch Jews began in the middle of Av 5702/1942.

“My father was considered a refugee from Germany,” says R’ Yosef, “and to the Dutch, he was considered German. Every day, he had to go to the immigration police station to get a certificate that he wasn’t hiding but was under their watchful eyes. Nobody should think for a moment that the Dutch treated the Jews any better; on the contrary, the Dutch collaborated with the Germans to kill as many Jews as possible and, unfortunately, were quite successful.”

In the middle of 5703, Yosef, who was not yet a year old, was deported to Westerbork from where Jews were sent to Auschwitz and other extermination camps. The Jews of Amsterdam were ordered to gather in the municipal theater. They were told they were going to labor camps which was a lie.

“Everyone brought a suitcase along with them, with the items needed in a labor camp,” said R’ Yosef sadly. “My father naively brought along an alarm clock because he heard that they would have to get up very early in the labor camp and those who were late were punished.”

By the way, the clock still exists; a pathetic reminder of those terrible times.

His mother, Elaine Sofia, may Hashem avenge her blood, was separated from her husband and son and taken directly to Sobibor in Poland. Her two brothers’ ends were also tragic.

“At an earlier point in the war, my mother had the opportunity to leave Holland and save her life. At the time, Dutch authorities were providing special travel permits to England for orphaned children or the sick. Each group consisted of 40-50 children and was accompanied by a male or female counselor. They went to England and stayed there. They left from Hoek van Holland (Port of Holland in English). My mother’s job was to escort the groups until the port.

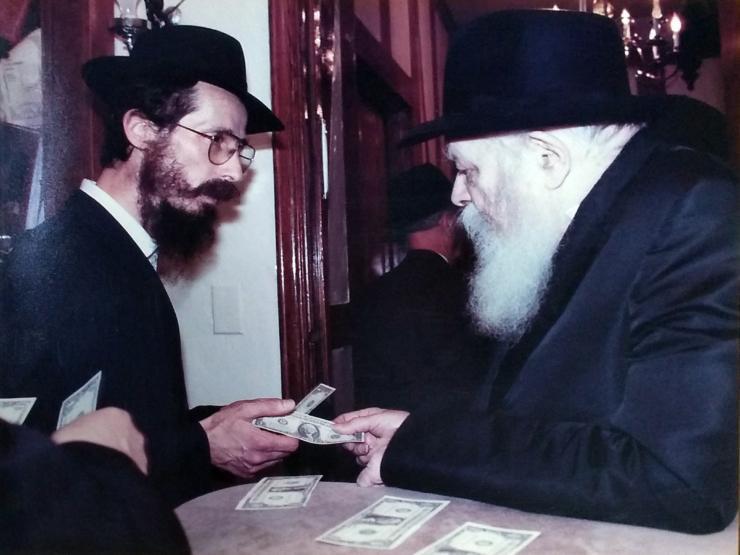

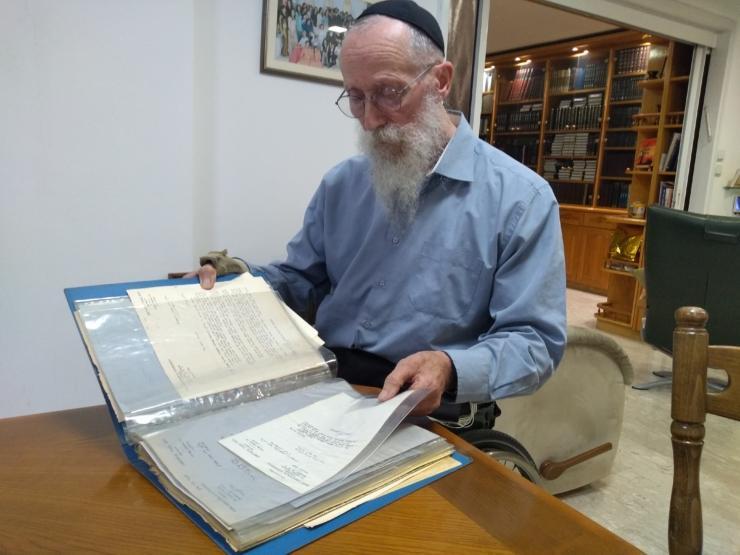

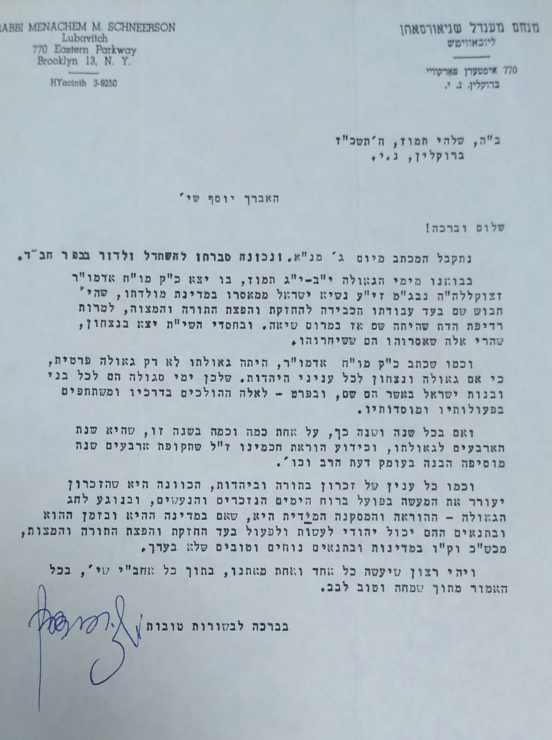

R’ Yosef with the folder of letters he received from the Rebbe

“One day, the people in charge told her they were missing a counselor and they offered her the position. It was quite an enticing offer for if she accompanied the group she could remain in London, thus saving her life. She responded, ‘No, I can’t join. I have a husband and two children and I won’t leave them.’”

While other branches of his family were being cut off, one after the other, by the Nazis, baby Yosef, who was with his father and sister in Westerbork came down with polio and was paralyzed in bed.

“For the orderly Germans, it was out of the question to have me get on the train lying down and our being sent to Auschwitz was pushed off again and again until the war ended.” Of course, Yosef has no recollection of the war years and whatever he knows was told to him by his father.

It turned out that it was his sickness that saved him, his father and sister Liz. They survived but Yosef had pneumonia several times and other illnesses.

“I remember that my father jokingly said to me, ‘When they ask you which diseases you had, you’re better off telling them which ones you didn’t have, because that list is shorter.’ Boruch Hashem though, the rest of my life I’ve never been sick. It seems that what I went through then, in the camp, toughened me up.”

SPIRITUAL AWAKENING

By war’s end, Werner remained alone with a young daughter and an even younger son who was sick with polio. R’ Yosef remembers liberation only vaguely. The tremendous grief over the death of his mother, whom he does not remember at all today, was diluted by necessity with his rehabilitation from illness. Yosef was given over to his aunts, his mother’s sisters, who showered him with warmth and love, while his sister recovered in Switzerland.

When the family reunited in Holland, Yosef was sent by his father, who had remarried a non-Jew in the meantime, to a rehabilitation orphanage that was opened for children who were injured in the war, so he would receive the best treatment for his condition. At that time, he did not even know he was Jewish. It was at the age of 10 that he heard from his father, for the first time, that they are Jews.

Were you surprised?

“No. The information meant nothing to me. I was still a child and reacted to it with equanimity. The atmosphere on the street was not anti-Semitic so I had no reason to feel inferior. I figured there are Jews just like there are dozens of other nations and races.”

Surprisingly, despite his lack of connection, his pintele Yid began to slowly wake up.

“I found it interesting that my father mentioned Jews in his conversations. For example, he would say, ‘Today, I met a Jew.’ I felt that there was something to this, about our being Jews. But when I brought up the topic and asked him to tell me more, he would change the subject.”

His father’s contradictory attitude toward being Jewish confused his son who began looking into religions.

“In the school library there were all kinds of books and I began avidly reading whatever had to do with religion. I read about Christianity, Buddhism and – l’havdil a million havdalos – about Judaism. At some point I said to myself: I was born a Jew, so why not check this out first?”

From his reading, Yosef concluded that being Jewish can’t be changed; born a Jew – always a Jew.

“One day, I said this to my father. ‘It won’t help how much you try to run away from your Judaism. You will always remain a Jew.’ I then said, ‘To the gentile neighbor, we will always be Jews. It’s an inseparable part of us.’ My father didn’t exactly identify with this approach. Interestingly, his opposition to my new path was greater than the opposition of the non-Jewish stepmother. Perhaps he did not want me to suffer because of our Jewish origins.”

Yosef’s conclusion was that they were Jews and they needed to live as Jews. At the age of 18 he joined a Bnei Akiva group. Then, at this stage of his life, Yosef met a Lubavitcher Chassid.

“His name was Rabbi Moshe Tuvia Fisher a’h. He came to Amsterdam from Yerushalayim and was a shliach for the Jewish Agency in Holland. Despite his apparent association with Bnei Akiva he was a Chabad Chassid with all his heart and soul and he infused Chabad standards into all the activities. He did not sit in his office and wait for people; he would go out and look for Jews and draw them to Yiddishkeit. He maintained high standards of tznius with the students (separate activities for boys and girls) and had certain times when he taught basic Judaism on various levels at the expense of the time devoted to general activities of the youth movement.

“R’ Moshe Fisher had a profound influence on the Bnei Akiva students. Since I was the oldest of the group, with the most serious questions, he devoted many hours to me personally and we truly connected on a soul level. Although I was part of the student body, at some point I became the person who helped him teach during the outings and activities.”

Yosef was captivated by R’ Fisher and decided to follow his way of life.

“I loved his mesirus nefesh. In addition to which, I saw that in Chabad every minhag is based on a long tradition. Also, the fact that people don’t operate as isolated individuals but have a Rebbe who guides them and directs them in the right direction, won me over.”

At a certain point, Yosef felt he could no longer live at home. The relationship with his father’s new wife ran into difficulties when she forced him to go to church every Sunday.

“I couldn’t eat anything at home because it was all treif.”

Yosef consulted with R’ Fisher who came up with an interesting plan.

“He told me I could take a counselor’s course offered by the Jewish Agency and then go back to the community I came from and become a Jewish Agency shliach there. This course entailed going to Eretz Yisrael for a year. Room and board were at the Agency’s expense.

“I thought this idea was fabulous for many reasons. It would get me out of a home which opposed all Jewish-religious activities and would enable me to become a youth leader in Holland. I began preparing to go and in the summer of that year I went to Eretz Yisrael for the first time.

“It was the most significant year of my life during which I became a proud, believing Jew. I studied Judaism and Jewish history thoroughly and strengthened my spiritual identity as a religious Jew.”

IT’S TIME TO WRITE TO THE REBBE

After a year, Yosef returned to Amsterdam and became active among the local Jewish youth.

“My official job was primarily office work, producing a seasonal brochure and assembling materials. I also helped R’ Fisher (who was there for three years). Our joint programming solidified my identity as a Chabad Chassid.”

Yosef also studied engineering at a local college. Due to his Shabbos observance, he was absent from college on Shabbos and Yom Tov. After three months he was called into the administrator’s office and was told that he must attend classes and take tests on Shabbos or leave. Yosef left.

From a young age he enjoyed working with glass and he took a course in optics. The course was compatible with Shabbos observance so, in addition to his work with youth, he studied optics for the next three years.

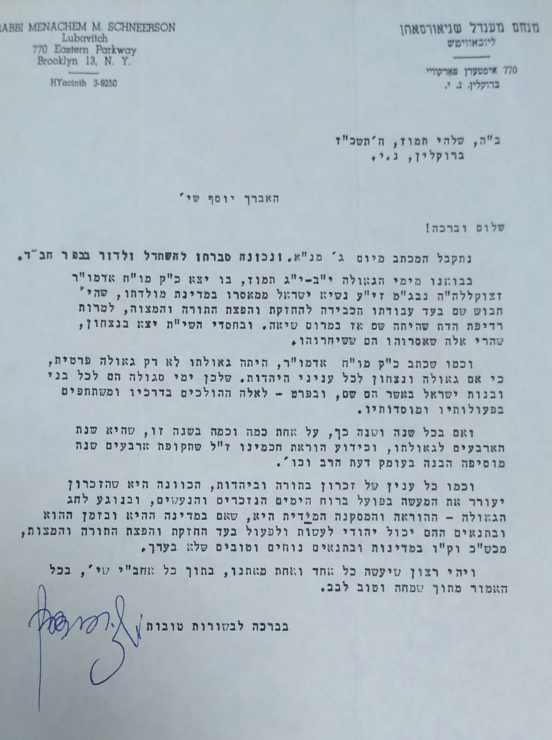

“One day, R’ Fisher told me that it was time for me to write to the Rebbe and tell him my life story and to ask him for a bracha for my new life and a shidduch, etc. When I asked what language to write in, he told me that the Rebbe knows many languages and I could write in Dutch.

“I wrote a long letter (even now, I am not willing to relate the contents) in the language I was accustomed to since childhood. The response from the Rebbe’s office began by gently saying that they were bringing to my attention that one could write to the secretariat in Hebrew, Yiddish and English, but after that line, I received an answer to everything I wrote.”

The Rebbe’s instruction to try and live in Kfar Chabad.

DANCING ON AND ON

Another Chassid who served as an inspiration for Yosef was Rabbi Yaakov Friedrich of Antwerp who went to Amsterdam often and held Chassidishe farbrengens to attract the youth. He also helped translate the Rebbe’s sichos into Dutch.

“At that time, the Forst family also became Chabad and, together, we were a solid group.”

R’ Yosef married Rosa, from a family that came from North Africa to France. She had been a madricha in Beth Rivkah in Yerres, France. The wedding was celebrated in the Chabad yeshiva in Brunoy.

“There was no band but the Chassidishe joy was tremendous,” says R’ Yosef who remembers the rosh yeshiva, Rabbi Yosef Goldberg a’h, “dancing and dancing nonstop.”

R’ Yosef wrote to the Rebbe asking where they should live. At first, they lived in a tiny apartment in Amsterdam where Yosef finished studying optics.

“After the good experience I had during the year I spent in Eretz Yisrael I wanted to live there, particularly Yerushalayim,” but when he sat down to write the letter, R’ Friedman suggested that he also write the option of living in Kfar Chabad. Yosef wrote whether to stay in Holland or move to Eretz Yisrael and live in Yerushalayim or Kfar Chabad.

The Rebbe’s answer, which first came a year later, at the end of Tammuz 5727/1967, said, “Your letter of 3 Menachem Av was received and his consideration is correct to attempt to live in Kfar Chabad.”

Just like that, the couple packed up their few possessions and moved to Eretz Yisrael. As soon as they arrived, they spoke to the vaad of Kfar Chabad about the explicit instruction from the Rebbe to live there. To their great disappointment, they were coldly received. The heads of the acceptance committee told them there was no place and they had prior obligations to those who were coming out of Russia. And anyway, what the Rebbe said wasn’t an order but a recommendation.

R’ Yosef, who failed to comprehend how they were preventing him from carrying out what the Rebbe said, showed them the letter but their response was to speak to a rav and do what he said.

R’ Yosef went to the rav of Kfar Chabad, Rabbi Shneur Zalman Garelik and told him the Rebbe’s answer and the response of the committee. The rav took a paper out of his drawer and ordered the members of the committee to find suitable housing for them and to immediately accept the Barnes couple in the Kfar.

“The members of the committee had to obey. However, that summer, there was nothing available, not to buy and not to rent. Having no choice, we lived in Bnei Brak for a year and a half and were put on the waiting list to rent in Kfar Chabad.”

It was first in 5729 that something became available and the Barnes family moved to Kfar Chabad.

DIFFICULTIES ACCLIMATING

It wasn’t easy settling in Kfar Chabad. Rabbi Yochanan Safranai, originally from Rotterdam, was able to help them a bit to acclimate and still, life in Eretz Yisrael was very hard.

Yosef, who had come with his certificate in optics, looked for a job in his field.

“An optician is the one who makes lenses for glasses. He is not trained to examine eyes and say how strong the lenses need to be.”

He wasn’t able to find a job and considered looking for work in Yerushalayim. In the end, he found a job in Tel Aviv.

“It was a job under difficult terms with a low salary. I realized that I needed to also study optometry to make a better living.

“I corresponded with the authorities in Holland and asked how I could advance my position to optometrist. They wrote that I could take a two-and-a-half year course in Holland. Since I was fed up with life in Eretz Yisrael I considered returning to Holland to live. I kept these thoughts to myself, and to my wife and others I said I was going to Holland to study and then return to Eretz Yisrael.”

It turned out that life in Amsterdam wasn’t all that simple which is why the idea of remaining there was dropped. The Barnes and their two children, with a third on the way, returned to Eretz Yisrael.

In the meantime, new housing had been built in ‘the neighborhoods’ and the Barnes, who had registered for an apartment there long before, were able to immediately move into their new home on the first floor of building 218. This time, thing were much easier.

“With my diploma as an optometrist, I soon found work at an optical store in Rechovot with satisfactory conditions.”

What was it like to move from a modern city like Amsterdam to life in the Kfar of those days?

“It wasn’t easy. It was like going back many decades in time. In addition to the difficulty in connecting to the social fabric of the community, the intermittent transportation was nerve-wracking. Also the infamous, inexact Chabad time drove me crazy since I was a Yekke. I looked for an opportunity to leave the Kfar. I even wrote to the Rebbe a few times about wanting to move to Yerushalayim or return to Holland but did not receive a reply.

“At that time I had an offer to buy a ground-floor apartment in Rechovot near my place of work. The house was in a quiet area with a big yard. Just to be sure, I spoke with the mayor about any plans of developing the area and he told me that the area near the house was preserved as a ‘green area’ and was designated as a public park; also, there would be no construction there in the future. I thought it was my lifetime opportunity and it would be the house of my dreams.

“When I did not receive an answer from the Rebbe about this, I decided to fly to see him for the first time in my life and ‘get his approval’ for me to leave the Kfar and move to Rechovot.”

R’ Yosef went to the Rebbe in 5733. He was marked down for a yechidus and prepared for the event, spiritually and emotionally.

“When I went in to see the Rebbe, even before I said a word, the Rebbe smiled and said in Yiddish, ‘Kfar Chabad is very good for you.’

“Obviously, the entire yechidus was completely different than what I had planned. I understood that there was nothing to pursue with that issue and spoke with the Rebbe about various personal matters that, until today, I prefer to keep to myself. My first yechidus was 20 minutes long! At first, the Rebbe spoke in Yiddish, a language I understood but at a certain point the Rebbe said, ‘I think you understand Lashon HaKodesh better,’ which was definitely correct, and the Rebbe spoke in Lashon HaKodesh.

“I left the yechidus with a good feeling with the dream of the house in Rechovot set aside, and that was a good thing. I found out that the mayor would take bribes from contractors and a few years later he was caught and put in jail. All construction plans made in his time were changed. Instead of a public park, apartment houses were built and the small, private house that I had wanted to move to was swallowed up among them. Within a few years, ‘my house’ became the center of one big construction site.”

Once he found out that the move from the Kfar was not happening, R’ Yosef decided to be independent. He opened an optical store in Ramle and hoped for the best.

“Since there was already an optical store in Ramle they all told me there was no reason to open another one. Some suggested that I bribe nurses at Kupat Cholim to refer those who needed glasses to me, but I told them all that I believe that G-d gives man his livelihood and I wasn’t willing to earn money through bribery. Boruch Hashem, despite all the warnings that I got that I wouldn’t succeed and would go bankrupt, the store still exists today.”

SEEING THE REBBE

After that yechidus, R’ Yosef was able to go to the Rebbe several more times. One of the times was when he won a raffle for Yud Shevat 5741. He signed up for the raffle only in order to participate but not to win since he had recently been to the Rebbe.

“I remember that when I was in my car on my way to work, I asked my wife to pay for us to participate in the raffle. Then, I won and I took my son Avrohom with me to the Rebbe.

“Since I had won the raffle, I had yechidus with my son on 16 Shevat. I gave the Rebbe a list of the participants in the raffle as well as a big bundle of letters and panim that I was given by the residents of the Kfar and Chassidim from all over the country. The Rebbe quickly went through the list of participants and I noticed that the Rebbe looked at each name.

“As you’ve noticed, I don’t tell what happened in my yechidus with the Rebbe, but I’ll tell you some of the yechidus that had to do with my son. That year, the Rebbe had started Tzivos Hashem. In the yechidus, the Rebbe asked my son whether he is a soldier in Tzivos Hashem. In those early days, the new youth movement was stronger in the United States than in Eretz Yisrael so my son said he didn’t know what it was.

“The Rebbe began to explain to him, patiently and in simple words, what Tzivos Hashem is, and that there are ranks with a child starting out as a private and rising in rank, with the Rebbe listing the ranks until he reached ‘general.’ The Rebbe wished my son that he report to the Rebbe that he became a general.

“I also went to the Rebbe in 5750 to attend a yechidus klalis and to receive a dollar. I was also in touch by letter but these are things I prefer to keep to myself.”

LIVING AS A PROUD JEW IN HIS FINAL YEARS

R’ Yosef Barnes has six children and many grandchildren. He considers this his personal victory over the Nazis who annihilated part of his family. The most moving point of all has to do with his father who passed away 22 years ago.

“Over the years, my father was disconnected from Judaism but in the two years before he died, when he was 94, he moved to Eretz Yisrael and lived in Hertzliya. Upon landing in Eretz Yisrael, he took a kippa out of his pocket and wore it to his final day.”

Beis Moshiach magazine can be obtained in stores around Crown Heights. To purchase a subscription, please go to: bmoshiach.org

153

Join ChabadInfo's News Roundup and alerts for the HOTTEST Chabad news and updates!