Today: Rabbi Marlow’s 23rd Yahrtzeit

In honor of the Yahrtzeit of the member of the Crown Heights Beis Din – Abir Sheb’abirim – Harav Hagaon, Harav Yehuda Kalman Marlow, A”H, we are presenting an article going through his life and stories of him • Full Article, Photos

Moshiach Weekly

“In the past, it was necessary to make sure that in addition to a rav there would also be a mashpia. This was because a rav would teach nigleh d’Torah along with practical halacha, and a mashpia would teach pnimiyus ha’Torah with its practical application. However, regarding rabbanei Lubavitch, they have both advantages. Thus, they are one unified whole.” (Sicha Motzaei Shabbos Truma 5748).

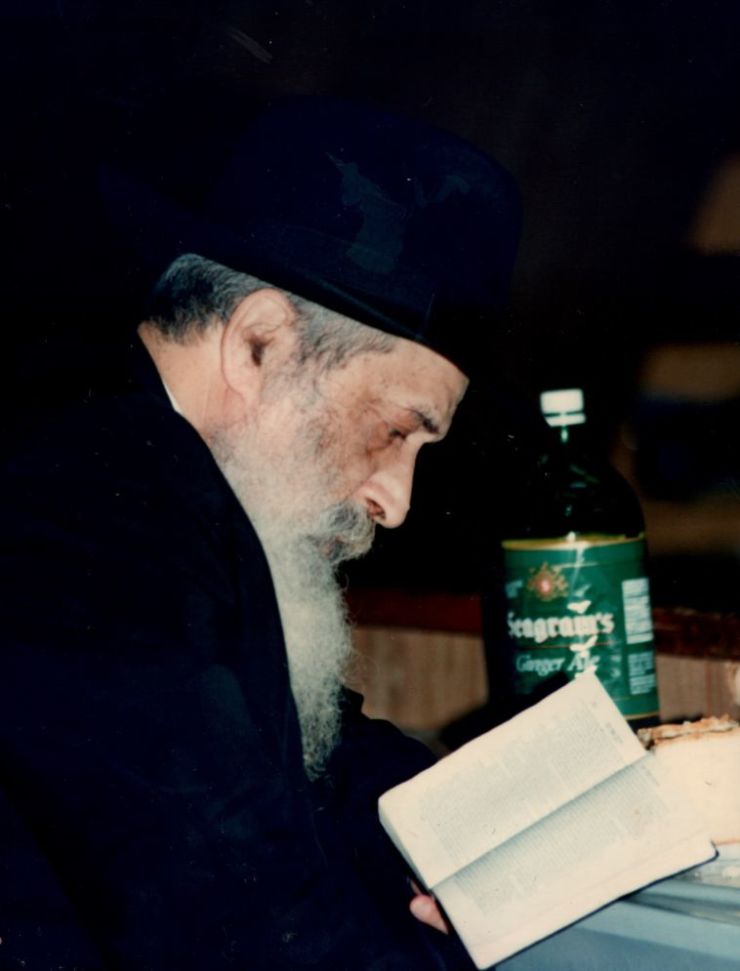

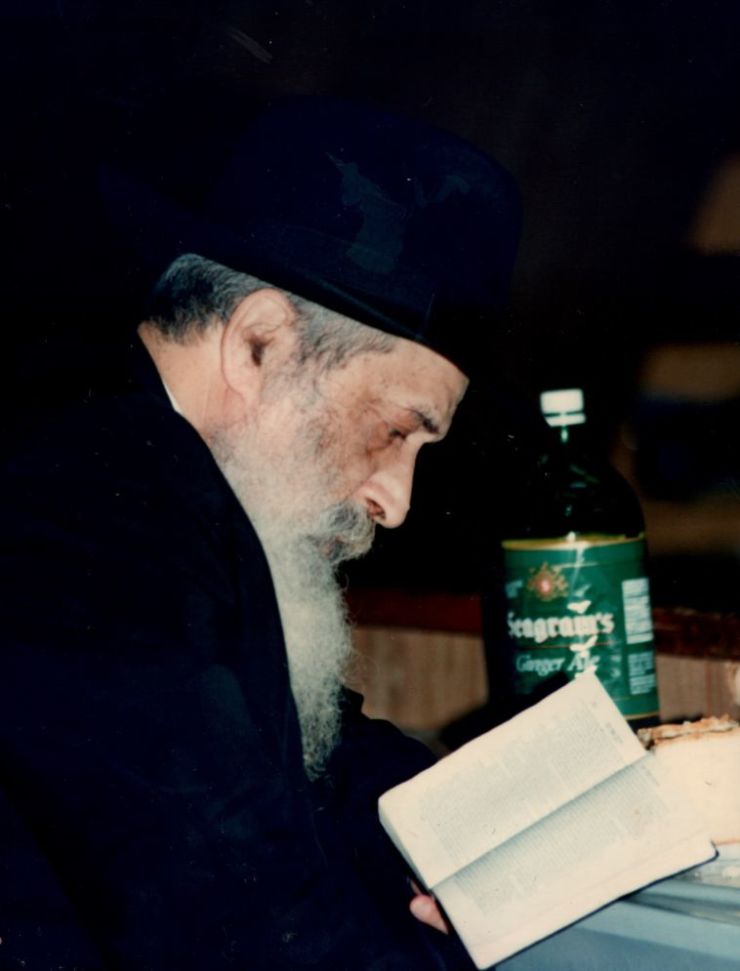

This description was fully realized in Rabbi Yehuda Kalman Marlow, who was an expert in halacha as well as a Chassid permeated by pnimiyus ha’Torah and pnimiyusdike Chassidic ways.

HIS CHILDHOOD

Rabbi Yehuda Kalman Marlow was born on 10 Adar Rishon 5692 (1932) in Frankfurt, Germany. His father was R’ Avrohom Yehoshua Malinovsky, who greatly admired Torah scholars. His mother, Rochel, descended from a well-known chain of rabbis, first among them the great gaon R’ Heschel, av beis din of the Cracow community. In his work Sheim HaGedolim, the Chida wrote about him that “there are many rabbis and gaonim among his descendants, the holy ones that are in the land of life. Among the living rabbis and gaonim of the generation, his grandchildren and relatives, may their names be eternal, so may it be G-d’s will.”

After the rise of the Nazi party, life in Germany became intolerable, and in 5699 the Malinovsky family immigrated to the United States and settled in Newark, New Jersey, where they shortened their name to Marlow. R’ Avrohom refused work opportunities that involved chilul Shabbos, and preferred demeaning and difficult work as long as he could remain shomer Shabbos. Six-year-old Yehuda Kalman endured great hardship, as there were times that he simply went hungry. This experience, however, educated him to stand up for his principles under the most trying circumstances.

Despite the difficult financial situation, R’ Avrohom Yehoshua sent his young son to learn in Torah Vodaas, where he was first introduced to Chabad Chassidus through Rabbi Shalom Dov Ber Gordon (may he have a refua shleima). Rabbi Gordon was a young Lubavitcher who had immigrated to the U.S. a few years before, and began disseminating Chassidus in Jewish schools.

Although R’ Avrohom Yehoshua was not a Chassid, he loved the Chassidic lifestyle, and when the Rebbe Rayatz came to the U.S. he went with the Chassidim to the Rebbe’s farbrengen. Over the years, R’ Avrohom Yehoshua participated in the Rebbe Rayatz’s farbrengens on a number of occasions, and even had yechidus twice with the Rebbe. Sometimes he took his son along so that he could breathe the Chassidic atmosphere in the Rebbe’s court. Since young bachurim were not allowed to participate in the farbrengens, young Rabbi Marlow had to hide. When he became bar mitzva, his father asked for a yechidus for him, but the Rebbe was not well at the time and very few people were granted an audience.

On Shabbos, Yud Shvat 5710, Rabbi Marlow was in Newark, where he heard of the passing of the Rebbe Rayatz. He rushed to Beis Chayeinu and took part in the large funeral that took place the next day. By this time he had already transferred to Yeshivas Tomchei Tmimim in New York, and from time to time he would go to Crown Heights and participate in the Rebbe MH”M’s farbrengens.

On one occasion, Rabbi Marlow related that he had been at the Yud-Beis Tammuz 5713 farbrengen, at the end of which the Rebbe distributed mashke, telling each participant matters that pertained to the future. When Rabbi Marlow passed before the Rebbe, the Rebbe spoke to him for a longer time concerning the future. Rabbi Marlow didn’t hear everything the Rebbe said because of the noise in the beis midrash, but what he did make out was, “nehenin mimenu eitza v’sushiya” (they benefit from him, receiving advice and counsel).

IN YESHIVAS TOMCHEI TMIMIM

One year on his birthday, Rabbi Marlow had a yechidus with the Rebbe in which he was asked what masechta he was learning. After answering that he was learning Maseches Gittin, the Rebbe asked how he learned it. Rabbi Marlow said he learned the Gemara with Rashi, Tosafos, and commentaries. The Rebbe asked him, “And what about the poskim?” From then on, Rabbi Marlow put special emphasis on learning the practical halachic applications of whatever masechta was being learned in yeshiva.

At that time, Rabbi Marlow learned in Yeshivas Tomchei Tmimim in 770. He was known for his tremendous diligence, and his teachers predicted greatness for him. He received his smicha from the roshei yeshivas Tomchei Tmimim at a young age.

Rabbi Nachman Shapiro related an episode that he heard from Rabbi Leibel Groner. One night the Rebbe asked Rabbi Groner why the lights in the beis midrash were burning late at night. Rabbi Groner told the Rebbe that Rabbi Marlow was still sitting there learning sifrei poskim. The Rebbe asked him to shut all the lights except for the one directly above Rabbi Marlow. Due to his great absorption in his studies, Rabbi Marlow didn’t even notice Rabbi Groner enter the beis midrash and shut off the lights.

At the meal of Acharon Shel Pesach 5718, the Rebbe called Rabbi Marlow by his first name, asked him whether he had drunk the four cups of wine, and poured for him from the bottle of wine on his table. This kiruv (show of affection) expressed the special relationship between master and student, a student who didn’t leave his studies for even a moment.

SHABBOS MEAL AT MIDNIGHT

In 5719, Rabbi Marlow married Chaya Reicher. His wife’s mother had been murdered by the Nazis in a concentration camp, and his wife had been miraculously saved and had immigrated to America. She was welcomed with open arms by the Becker family, who adopted her as their daughter. The Rebbe was their mesader kiddushin.

At the time, Rabbi Marlow worked as a teacher in the Lubavitcher Yeshiva. After teaching in the morning, he would go to a shul where he sat and learned assiduously. He would return home late at night.

Rabbi Marlow had a special program of study on Shabbos. After davening he would put two tallis bags full of s’farim down on the table and would study them in a certain order, generally until 11:00 p.m. Only then would he return home for the Shabbos meal. His son, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchok Marlow, remembers that his mother would serve him the Shabbos meal before he went to Maariv so that he would be able to go to sleep right after Kiddush, which took place late at night.

On Shabbos Mevarchim Rabbi Marlow wouldn’t go to sleep at all. After the meal, he would nap in his chair for about two hours and get up and wash his hands. Then he would say Birchos HaShachar and begin reciting Tehillim. He would typically finish the entire book twice every Shabbos Mevarchim.

Each year, Rabbi Marlow would complete a number of mesechtos b’iyun, and on Erev Pesach, since he was a firstborn, he would make a siyum on a masechta and still he would fast. Fasting on such a busy day didn’t stop him from remaining in shul after Maariv for his regular shiurim. A few hours after the last person left the shul, the Rav would go home to break his fast and make the seider.

The Rav’s son-in-law, Rabbi Yosef Ben-Tzion Schechter, remembers the seider night as a very special experience. “The Rav would sit and read the Hagada in an especially intense way, enunciating each word exactly the way we say ‘Hashem hu ha’Elokim’ in T’fillas Ne’ila.”

A WALKING SHULCHAN ARUCH

Although the Rav tried to hide his erudition, he couldn’t conceal his tremendous diligence from all those who saw him in shul. They always saw him sitting in his corner, delving deeply into his s’farim. Some people began approaching him with their halachic queries, and discovered that the Rav was fluent in all of the Alter Rebbe’s Shulchan Aruch by heart, word for word. More and more people asked him questions and he became an unofficial rav.

The Rav in Crown Heights at the time was Rabbi Zalman Shimon Dvorkin, a’h, who spoke mostly in Yiddish and wasn’t that comfortable in English. Baalei teshuva who joined the community couldn’t communicate with Rabbi Dvorkin and preferred asking Rabbi Marlow their questions. Rabbi Marlow, however, did not want to “pasken in the presence of his teacher” and would, therefore, not answer directly; he would open the Shulchan Aruch to the section that addressed the topic and learn it with them until they understood what to do.

Rabbi Marlow acquired his incredible proficiency in Shulchan Aruch through his intensive studies. Before every Yom Tov he reviewed all the pertinent halachos in depth, and he had a special program of study for the halachos that apply all year round.

When Rabbi Marlow would lie down for a brief rest before Pesach, he would ask his son to sit near his bed with a Shulchan Aruch and test him on the index at the back. His son would say a certain topic and the Rav would respond with the simanim that dealt with the topic. This was Rabbi Marlow’s rest on Erev Pesach.

Aside from his incredible mastery of Shulchan Aruch and other halachic works, the Rav knew the entire Torah by heart with Rashi’s commentary and Targum Unkelus. “He knew Targum Unkelus like we know Ashrei,” testifies his son-in-law Rabbi Schechter. He was also an exacting baal korei, fluent in the taamei ha’mikra. His son relates that in the last weeks of his life, when there was a minyan in his house, the Rav, confined to bed and unable to look inside a Chumash, would nonetheless correct the baal korei, Rabbi Levi Yitzchok Garelik, on even minor errors.

Presumably the Rav was knowledgeable in sifrei Kabbala, too. R’ Yosef Brook, who worked alongside Rabbi Marlow for the last fourteen years, once heard a rav who was involved in building mikvaos say that for years he wondered why round mikvaos weren’t built. He had asked dozens of rabbanim and nobody had an answer for him. When he asked Rabbi Marlow, the Rav answered him on the spot that it was based on Kabbala, and referred him to a Kabbalistic source giving the reason.

The Rav’s memory was truly awesome; whatever he learned or heard he remembered. In later years, after he was elected rav, he began officiating as mesader kiddushin. After writing the tenaim and the k’suba with all the details of the cosigners and the witnesses, etc., he would give the k’suba to the chassan and read it through again in order to ensure there were no mistakes. Some people noticed that the copy the Rav held was blank, without the names of the chassan, kalla, witnesses, etc., and although he had only heard the names one time, the Rav read from the blank copy as though he were reading from the k’suba itself.

THE INCIDENT IN THE SUCCA

When the Rebbe MH”M ate the Yom Tov meals on the second floor of 770 with the ziknei ha’Chassidim, young men would ask the Rashag (the Rebbe’s brother-in-law) interesting questions so that he could bring them up at the meal, and the Rebbe would answer them.

On Succos 5730, Rabbi Marlow asked the Rashag why the Chabad custom is not to sleep in the succa, although al pi din there is an obligation to do so. He also asked why Chabad Chassidim are extremely stringent about not eating or drinking outside the succa, even under circumstances when al pi din they could be lenient.

The Rashag asked the Rebbe, and at the farbrengen on the second day of Yom Tov, the Rebbe referred to the question and explained the Chabad custom at length. After finishing the explanation, the Rebbe smiled and said that since “all who delve into the laws of sleeping are as if they are actually sleeping,” they should sing a happy niggun. The Rebbe strongly encouraged the singing, and the large crowd danced in place with vigor.

Then, one of the piles of benches making up bleachers collapsed, crushing Rabbi Marlow’s leg. Despite the terrible pain, the Rav didn’t say a word so as not to disturb the farbrengen. The organizing committee rushed over and began moving people aside. The Rav was at this point lying on the ground, and when they tried moving him, they noticed his leg crushed under the fallen benches. The singing had stopped and the Rebbe looked grave as he kept looking at that spot.

After great effort, they managed to get the Rav out. Then they brought him to the hospital for emergency treatment. The Rav’s leg was in a cast for six months, and some have said that the Rebbe showed concern about every stage of the treatment. At that difficult time, one could see how particular the Rav was about taking a daily mikva. As soon as he was able to, while still in his cast, the Rav went to the mikva and immersed, keeping his leg out of the water.

Rabbi Aharon Chitrik, who had been standing near the Rav when the benches fell, relates that on Motzaei Simchas Torah of that year, two of the Rav’s friends went to visit him in the hospital and brought him on crutches to the Rebbe’s farbrengen. The Rebbe was in the middle of a sicha as they entered, and the Rav stood off to the side so as not to attract attention. When the sicha was finished, the Rebbe looked in his direction and motioned for them to bring him up to the bima and give him l’chaim.

After the break between sichos, the Rebbe said that this was the time to finish the topic they had begun on Succos about the Chabad custom of not sleeping in the succa. After that sicha, the Rav said that he realized that the Rebbe knew exactly who had asked the question, and he felt that this was the Rebbe’s way of saying welcome.

On Succos, the Rav acted stringently and did not go to sleep. Even this year, weak from his terrible illness, he did not get into bed from the beginning of Yom Tov until Motzaei Simchas Torah. He danced at night at the Simchas Beis HaShoeiva, and at most, would nap in his office while sitting in his chair.

THE ELECTIONS FOR THE RABBANUS

On Motzaei Shabbos, 17 Adar 5745, Rabbi Dvorkin, Rav of Crown Heights, passed away. Less than a year later, elections were held in which the residents of Crown Heights selected three rabbanim: Rabbi Marlow, Rabbi Avrohom Osdoba, and Rabbi Yosef Heller. Rabbi Marlow was elected with a stunning majority of over 800 votes out of 1,000 possible votes! It was only natural that Rabbi Marlow be selected as mara d’asra of the community after serving as a member of the beis din rabbanei Lubavitch, headed by Rabbi Dvorkin, for years.

The Rebbe was personally involved in the election process. When certain askanim tried to interfere with the elections, the Rebbe uncharacteristically stated (sicha Shabbos Mattos-Massei 5746), “When I saw the situation, I had no choice but to put everything else aside to ensure that everything about the elections for rabbanim be according to the Shulchan Aruch.”

The Rebbe made another interesting comment in the sicha of Shabbos Mishpatim 5747: “Crown Heights is one of the few communities in which the rabbanim were elected by the entire tzibur. All men of the community were called upon to personally participate in the elections, and most responded and came to a holy location, a beis knesses and beis midrash, particularly the beis knesses and beis midrash of the Rebbe, my father-in-law, nasi doreinu, where they themselves elected the rabbanim, a fact which gives the rabbanim the greatest possible authority.”

In that sicha, the Rebbe recited the statement of our Sages and applied it to the rabbanim of the community: “Yerubaal in his generation was like Moshe in his generation…Yiftach in his generation was like Shmuel in his generation…when a leader is appointed over the tzibur he is like the mightiest of the mighty [abir she’be’abirim]…you may only go to the judge of your times!”

The Rebbe continued, “It makes no difference whether this fact pleases them or not. It is the same as the fact that they weren’t consulted about the giving of the Ten Commandments, the 613 mitzvos of the Torah, and everything a scholar will innovate in the future, long before he and his father were born, as well as those who educated him to conduct himself in this way. The reality is that these rabbanim were elected by the majority of the community, and they will continue to serve in this rabbanus until the coming of the righteous redeemer!”

Another sicha that dealt with the special position of Chabad rabbanim was said on Motzaei Shabbos Truma 5748 after the conclusion of shiva for Rebbetzin Chaya Mushka, a’h. After that famous sicha, the rabbanim of the community, led by Rabbi Marlow, went to the Rebbe’s home. Rabbi Marlow spoke along the same lines as the Rebbe’s sicha, saying we are in the week of Parshas V’Ata Tetzaveh, and we all know who the “V’Ata” [and you] is. So the Rebbe will surely have length of days and good years. The Rebbe listened to Rabbi Marlow and then said with a smile, “but it should be without the ‘kasis la’maor’ [crushing].”

On Erev Pesach 5747, the first Erev Pesach after being elected rav of the community, the telephone at Rabbi Marlow’s house rang at the time of bedikas chametz. Rabbi Chadakov, the Rebbe’s secretary, was on the line, and he told Rabbi Marlow that the Rebbe asked that he come to 770. Rabbi Osdoba and Rabbi Heller were there, as well. Rabbi Chadakov told them in the Rebbe’s name that during the year between Rabbi Dvorkin’s passing and the elections, the Rebbe had sold his chametz to Rabbi Yisroel Yitzchok Piekarsky. Since you cannot sell chametz to three rabbanim, this year the Rebbe would sell his chametz to Rabbi Piekarsky again. However, since they were the rabbanim of the community, the Rebbe asked that each of them be given a hundred-dollar bill. From that time on, every Erev Pesach, the rabbanim received a hundred-dollar bill from the Rebbe.

In Cheshvan 5750, the Rebbe wrote: “Obviously I am satisfied with the Vaad HaRabbanim shlita of the community. May they have length of days and years over their kingdom.”

Rabbi Yitzchok Gansburg remembers that at one of the farbrengens, the Rebbe shouted about the fact that people don’t cry out “ad masai” enough. Rabbi Gansburg was disturbed by what the Rebbe said, and he asked the Rebbe, “What does the Rebbe want of us? We are screaming, crying, and pleading!”

The Rebbe responded, “Crying? It’s forbidden to cry on Shabbos.” After pointing in Rabbi Marlow’s direction, the Rebbe said, “There is a rav here who will declare that it is forbidden to cry on Shabbos. Rabbi Marlow was standing very close to Rabbi Gansburg and he quietly said that it was forbidden to cry on Shabbos, but the Rebbe wasn’t satisfied. He asked the Rav to stand in his place and loudly announce that it was forbidden to cry on Shabbos. Only after the Rav did so did the Rebbe begin a happy niggun, and the farbrengen continued.

Rabbi Shneur Zalman Lipsker of Philadelphia relates that back in 5737, the Rebbe had already told Rabbi Marlow to become a rav mora horaa. This is how it came about:

That year, the N’shei Chabad produced a cookbook and Rabbi Marlow was the one responsible for the halachic aspects of the book. After the book was printed, Rabbi Marlow gave the Rebbe a copy of it at a farbrengen. Rabbi Lipsker, who was standing nearby, heard the Rebbe say, “Enough already being nechba el ha’keilim (i.e. humble). The time has come for you to be a mora horaa to the public!”

Rabbi Yitzchok Hendel, av beis din and rav of the Chabad community in Montreal, said that he once heard the Rebbe refer to Rabbi Marlow as an ish halacha.

A LEADER IN INYANEI MOSHIACH AND GEULA

Rabbi Marlow had a special chayus in all inyanei Moshiach and Geula, especially on the topic of Moshiach’s identity. The Rav used every opportunity to encourage activities of this nature and he participated, as well.

It was a blustery winter day in early 5747 (1986). 770 was brimming with Bochurim just going about their regular learning regimen, as well as some balabatim still finishing off the morning Shacharis prayers. All were completely oblivious to that which was about to transpire.

Then, as if the sound barrier had been broken, the prevailing serenity was shattered by the earth-shaking news: Didan Notzach! After an anxious year-long wait, the federal court finally ruled in favor of the Rebbe, that the Frierdiker Rebbe’s library belongs to Agudas Chasidei Chabad.

The Bochurim broke out in spontaneous joyous dancing, slowly joined by the throngs of Chassidim who flocked to 770 to take part in the festivities.

The celebrations lasted for a full week, manifesting itself in exuberant dancing and lively Farbrengens. Every day of that week the Chassidim also merited hearing a Sicha from the Rebbe.

When Shabbos Parshas Vayigash arrived, the first Shabbos following the ruling, the Chassidim’s expectations were high. This would be the first Farbrengen with the Rebbe since the ruling. And indeed, they were not disappointed. At that week’s Farbrengen the Rebbe spoke very strongly about Moshiach and the need to demand his arrival through the cries of ‘Ad Mosai!’ After one of the Sichos, the Chassidim broke out in a sustained chant of Ad Mosai.

Sitting at that Farbrengen was the Rov of Crown Heights, Rabbi Yehuda Kalman Marlow. He quickly made up his mind that he would not let the Rebbe’s words linger solely in chants and slogans, but that they must be channeled into concrete actions. So, that very night, he gathered a group of twenty five Rabbonim to discuss what they can halachically do regarding this issue.

At that meeting, Rabbi Marlow inked out an extensive Psak Din ruling that Moshiach must come without delay. The Psak was signed by all those in attendance.

The following morning, Rabbi Marlow, along with some other Rabbonin, positioned themselves in Gan Eden Hatachton, near the entrance to the Rebbe’s room, in order to hand the Psak to the Rebbe.

Upon receiving the Psak, the Rebbe leafed through it for some time and then blessed the Rabbonim that indeed Hashem should carry out the Psak by bringing Moshiach without further tarry.

This would be the first Psak Din, though not the last, signed by Rabbi Marlow regarding the coming of Moshiach.Also, in the summer of 5751, when the rabbanim were writing piskei dinim that the time for the Geula had arrived and that the Rebbe is Melech HaMoshiach, Rabbi Marlow was in the forefront of these activities.

In the period after Gimmel Tammuz, Rabbi Marlow joined the activists who continued to spread the besuras ha’Geula. Among other things, Rabbi Marlow was the official rav of this publication and a member of the hanhala ruchnis of the Chabad World Center to Greet Moshiach.

The Rav had come for his first visit to the Holy Land in 5755, but since it was so close to Pesach, he had to return home that same night. He gave a notable speech at the huge kinus on Beis Nissan that year in Yad Eliyahu in Tel Aviv. The Rav’s speech was all of three minutes, but more was unnecessary. The following words speak for themselves: “All the rabbanim and those gathered here, gathered here this evening in order to strengthen the belief in Moshiach and the fact that Moshiach is here with us. I am privileged to represent the Crown Heights community — ‘Kan tziva Hashem es ha’bracha’ — which is here in spirit, and participates along with all those gathered in “a land which has G-d’s eyes upon it from the beginning of the year until the end of the year,” and to represent all those who proclaim and shout ‘ad masai.’

“It is important to note that today, ten months have passed (from Gimmel Tammuz to Gimmel Nissan) and we find ourselves in a situation which even further emphasizes the cry of ‘ad masai.’ The main thing is to conclude on a positive note: Today marks seven years since the Rebbe Melech HaMoshiach informed us about ‘Yechi.’ I represent, as I said, the Crown Heights community, who make this proclamation here in Eretz Yisroel: ‘Yechi Adoneinu Moreinu v’Rabbeinu Melech HaMoshiach l’olam va’ed.’”

Apparently the deep impression made by the kinus was felt even by the Rav himself, for after he became sick, he asked to see the video of that kinus.

Rabbi Marlow’s final public appearance was at the kinus ha’yovel, which was organized by the Chabad World Center to Greet Moshiach on Erev Yud Shvat this year. The Rav spoke about the importance of the pure faith of children: “Unfortunately, today’s children never saw the Rebbe, yet they are still growing up as real mekusharim and maaminim b’emuna shleima [true believers]. As far as we are concerned, we actually saw the Rebbe. But from where do the children get these kochos? The answer must be that these are very high neshamos with very special kochos. Otherwise there is no explanation.”

“THAT’S WHY HE’S THE RAV!”

Even after his appointment as rav, Rabbi Marlow was careful not to use that position for his personal benefit. Residents of the community would offer him a ride, but if the person didn’t live nearby and would have to make a special trip to the Rav’s home, the Rav would politely decline the offer, saying that he preferred to walk.

Rabbi Yekusiel Rapp, who lived in the same building as the Rav, relates that when they would both approach the building, the Rav would try to take his key out first so that it wouldn’t look as though he was using somebody to open the door for him. Rabbi Marlow always paid for his building’s communal succa early and was careful to pay a bit more just to make sure…

Rabbi Rapp was once standing in the bank when he saw the Rav enter and stand in line. Only one teller was available, and the long line crawled along. Rabbi Rapp told one of the managers that the Rav of the community was there and it wasn’t right that he stand in line with everyone else. The woman agreed and asked him to call Rabbi Marlow to her office.

When Rabbi Rapp went over to Rabbi Marlow and informed him that he could bypass the line, the Rav refused, saying it wouldn’t be a kiddush Hashem. Rabbi Rapp went back to the manager and told her that the Rav was humble and refused to leave the line. She remarked, “That’s why he’s the chief rabbi!”

Rabbi Marlow’s son-in-law, Rabbi Schechter, says that in the Rav’s final two months, he had to use a private mikva to make immersing easier for him. But the Rav was very careful not to take advantage of the mikva’s owner. When he arrived at this mikva once with his grandson, he made sure his grandson went to immerse in the communal mikva instead.

Rabbi Marlow’s son, R’ Yosef Yitzchok, who serves as rav in a Lubavitch shul in Miami, relates that there was once a great controversy in his shul. Throughout that time, his father refused to go and visit his shul, explaining that doing so might be construed as an attempt to influence people to side with his son.

“SMALL JARS”

After his appointment as mara d’asra and member of the beis din, a vaad ha’kashrus was established. The Rav would travel to various factories in order to check the kashrus of the products produced there. R’ Yossi Brook accompanied the Rav on these trips.

Before every trip, the Rav would prepare a briefcase of s’farim he would study while traveling. Peering into his s’farim, he was utterly absorbed in study. The long trips gave R’ Brook a wonderful opportunity to see how the Rav conducted himself. For example, he realized that every time they traveled at night, as soon as the sun rose the Rav requested to stop, and he put on tefillin and said K’rias Sh’ma.

Despite R’ Brook’s proximity, the Rav still managed to be discreet; it was only with great difficulty that R’ Yossi managed to discover a bit of the Rav’s ways. The Rav was particular not to drink water that had been in a metal container, even under circumstances when all the poskim say there is no problem in doing so. The amazing thing was that the Rav was able to hide this for over two years, even though they spent hours together nearly every day.

“The Rav never told me that he doesn’t drink water from a can. He would simply say he wasn’t thirsty. It took me two years to figure it out. I noticed that every time I bought a can the Rav wasn’t thirsty, but when I bought a bottle the Rav willingly drank. Once I realized this, I made sure to bring along bottles of drinks for the Rav.”

The Rav had a shiur in Shulchan Aruch with some baalei battim. R’ Brook said that the Rav always asked him to make sure they would return from their trips in time for his Wednesday class. Rabbi Meir Eichler, one of the participants of the shiur, related that the Rav’s devotion to the class inspired the other participants to feel a sense of responsibility to come to the class on time.

“When I married off my son Shemarya,” said R’ Brook, “I asked the Rav to come to the wedding, which took place in France. The Rav declined, afraid I would honor him with siddur kiddushin without the full consent of Rabbi Hillel Pevsner, the mara d’asra of the Lubavitch community in Paris. Although I promised him I wouldn’t do anything without Rabbi Pevsner’s explicit permission, the Rav was worried that Rabbi Pevsner would not give his wholehearted consent, so he did not come to the wedding.

“When I married off my daughter, at first the wedding was supposed to take place in Kfar Chabad, and once again the Rav absolutely refused to come to the wedding. Only after the wedding was scheduled to take place in the manufacturing district in Azor did the Rav agree to come. He came to Eretz Yisroel for one day to participate in the wedding.”

On the flight to that wedding, the Rav didn’t eat anything that was served. He only ate what he had brought from home – salty fish. Rabbi Meir Eichler, who accompanied the Rav on the flight, went to the kitchen to bring the Rav a cup of water, but to his surprise, the Rav did not touch it. He was certain the Rav was thirsty after eating the fish and he wanted to find out why the Rav wouldn’t drink the water. He realized that the cup he had brought was made of glass. Only after he replaced the glass with a plastic cup did the Rav take a drink.

They landed in Eretz Yisroel in the afternoon. The Rav wished to go to a mikva so that a day wouldn’t pass without immersing. After much effort they found an open mikva in Bnei Brak, and only then was the Rav at ease.

The Rav spent a total of 30 hours in Eretz Yisroel. When they suggested that he visit Yerushalayim, he politely refused. Only after he asked R’ Yossi whether you could see the hills of Yerushalayim from Azor, explaining that he didn’t want to get into a halachic problem about where you have to tear k’ria for the churban Yerushalayim, did R’ Yossi understand why the Rav had avoided going to Yerushalayim.

The Rav was particular not to eat food prepared outside his house. He went so far as not to drink a cup of coffee anywhere else, and he always took a thermos with him on trips. Once, when he was in a factory of G-d-fearing Jews, the owner asked him why he didn’t drink coffee from the machine in the office. The Rav said he would be willing to drink from it if Jews were the only ones who used the machine.

BAAL TZEDAKA

The Rav was a great baal tzedaka, and he did it all secretly. R’ Yossi Brook relates that once when they were organizing the Rav’s office, he noticed dozens of checks given to the Rav that had never been cashed. When the Rav received a check for being mesader kiddushin for a financially strapped family, the Rav would put the check aside. He did the same thing with checks sent to him for Pesach or the like. He never cashed these checks. When cash was pushed into his hands, the Rav quickly gave the money to charitable causes. Generally speaking, the Rav didn’t care much about his personal finances. In his office there were checks that had never been cashed simply because the Rav couldn’t be bothered.

The Rav tried to hide his acts of charity from people, and only occasionally would those close to him notice anything unusual. When he was in the hospital, a resident of the community called and told Rabbi Marlow’s daughter about a great kindness that Rabbi Marlow did for her a few years earlier.

Her son did not get along with the boys in the local yeshiva and she wanted to send him to Eretz Yisroel to learn, but she didn’t have enough money for the ticket. In desperation, the woman asked the Rav for advice. The Rav told her to order a ticket and he would take care of the cost. And that’s just what happened – the Rav paid for the ticket out of his personal funds, and the woman’s son learned in a yeshiva where he was successful.

In more recent weeks, when the Rav couldn’t personally distribute tzedaka, he would sit in bed and tell his daughter to write large checks for various causes. The Rav would give away nearly his entire salary. One of the gabbai ha’tzedaka in Crown Heights said that when he came to ask for tzedaka, the Rav would give him money as though he owed it to him.

The Rav did tzedaka with more than money. Someone once came to his office and told the Rav that his daughter was in the hospital in critical condition and the doctors wanted to take her off life support. He had tried unsuccessfully to dispute the doctors, and as a last resort he was asking the Rav if he could use his connections. The Rav calmed him down and told him that everything would be taken care of. This was on Hoshana Rabba at 9:00 a.m. That day, the Rav made telephone calls until 3:00 p.m. and only then was he able to ensure that the girl would not be removed from the machines. Then he finally left his office and went to 770 to daven Shacharis.

One of the Rav’s mashgichim for the milking of cows once felt heart pains in the middle of a milking and was taken to the hospital. Another mashgiach happened to show up after the first had left. When he heard what had happened, he called Rabbi Marlow and asked him what to do with the milk. The Rav told him that as far as the hechsher of the rabbanim, the milk was no good, since there hadn’t been a mashgiach constantly supervising it.

At the end of the milking, the mashgiach rushed to the hospital to visit his colleague. When he arrived at his room he saw his colleague talking on the telephone. After a quarter of an hour, when he finished the conversation, the mashgiach told him that he had been talking to Rabbi Marlow who had called to ask how he was doing. It seems that after hearing that the mashgiach had been hospitalized, Rabbi Marlow called all the hospitals in the area and asked whether a patient by that name had been admitted. When the Rav finally managed to locate him, he spoke with him on the telephone for quite some time in order to calm him.

THE RAV’S ILLNESS

After Tishrei of this year, the Rav felt unusually tired. At first he thought it was accumulated exhaustion, but after a few weeks, he realized it was far more serious. He was examined by doctors, who discovered a malignant growth near his brain. An operation was immediately scheduled.

The operation took place on 7 Kislev, and the Rav’s preparations included photocopying hilchos Chanuka from the Shulchan Aruch. The night before the operation, the Rav was hospitalized. He spent the night learning the Taz on hilchos Chanuka in depth. He was so immersed in his learning that he didn’t notice his son-in-law, Rabbi Schechter, coming in and out every half-hour.

Before the operation, the Rav asked his son to remind him to daven Maariv after the operation. Due to the tension and concern for his father, his son forgot his father’s request. At 4:00 a.m.. when he entered his father’s room, his father asked him, “You came to remind me about davening Maariv? It’s all right, I davened already.”

“Think about it,” says his son emotionally. “My father underwent a serious operation on his head, in the course of which they opened up his skull. We’re talking about severe pain, from which a normal person would take days to recover, yet he managed to remember that he had to daven Maariv!”

The Rav was truly amazing. Even in his final days, when he found it hard to read, he made sure to complete the daily shiurim of Chitas and Rambam – shiurim which he never missed for even a day since the takana was established.

After the first operation, when he returned to the hospital, the Rav wrote a letter to the Rebbe, which he put in the Igros Kodesh. In his letter, the Rav asked for a bracha that he should not become a burden to his family during his illness. What bothered him, when his life hung in the balance, was that he shouldn’t be a burden to others!

Rabbi Marlow’s strong faith in the Rebbe MH”M expressed itself even during his illness when the doctors confined him to his bed. On the first Shabbos after the operation, ten bachurim from Yeshivas Tomchei Tmimim – 770 came to daven Kabbalas Shabbos with him in the hospital. Before they began, the family asked them to daven fast because of the Rav’s condition. At the end of “Lecha Dodi,” the Rav motioned to them to dance “Yechi” as customary. When the Rav noticed their hesitation, he got up from his chair and began dancing and singing “Yechi” himself. The dancing went on for ten minutes, and the Rav returned to bed exhausted. The effort was so great that after davening he could not make Kiddush and he had to rest for two hours. It was actual mesirus nefesh in order to dance to “Yechi.” After he got up he told his family, “It was a special davening,” and then made Kiddush.

In the final months of his illness, there was noticeable concern in all Lubavitch communities, particularly in Crown Heights. Tefillos were added on behalf of the Rav, and people learned hilchos Shabbos as a z’chus for the Rav (as suggested by Rabbi Osdoba).

On the last Tuesday of his life, as he spoke with his son on the telephone, he began the conversation by saying, “A gutten erev Shabbos.”

590

Join ChabadInfo's News Roundup and alerts for the HOTTEST Chabad news and updates!