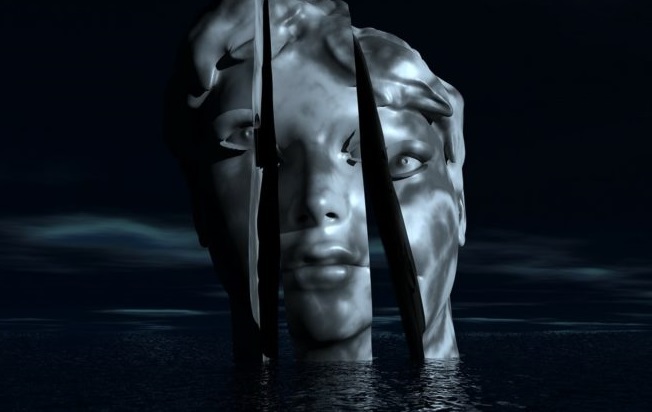

Chassidus as an Eclectic Psychological Approach

There are many schools of thought in psychology and each has its own shortcomings. Chassidus offers a complete approach based on the anatomy and physiology of the soul • Writen by Rabbi Shraga Crombie • Full Article

By Rabbi Shraga Crombie

Translated from the original Hebrew by Rabbi Yonah Pruss

A number of central schools dominate today’s world of psychology.

In recent years many attempts have been made to present an integrated approach to overcome existing deficiencies in each of them, based on the understanding that none of the existing approaches provide an adequate response to the structure of the psyche and mental problems.

Chassidic teaching is the solution to this problem because it offers a theory of the mind that combines the virtues of each of the different methods, but without their disadvantages, and indeed adds to them.

According to Chassidus, man possesses depth and is susceptible to spiritual conflicts (the psychoanalytic approach), yet he is inherently good and aspires to fulfilment (the humanistic approach), he is also measured in his actions and influenced by the environment (the behaviourist approach), but of course his personality is also composed of thoughts and emotions (the cognitive approach). In other words, man is a complex being, striving for fulfilment and transcendence of his nature, influenced by (and influencing) both the environment and internal processes.

Although the above can be seen as a mere collection of several existing approaches, in truth it is nothing less than a conceptual revolution that can bring about a great change in the understanding of the human psyche.

In order to present the approach to treatment according to Chassidic teachings, we will briefly review the central ideas in each of the psychological schools, pointing to their virtues and shortcomings, and compare them with the teachings of Chassidism. Thus, it becomes clear that Chassidus is the ultimate answer to the understanding of the soul and therefore the right path to mental health and personal well-being.

Psychodynamic Theories

Modern psychology has made a huge breakthrough since Sigmund Freud, an assimilated Jew from Vienna, began to spread his ideas known as psychoanalysis or psychodynamics.

Over the past hundred years, the psychodynamic approach has been attacked from many different directions, and its status has been cast into doubt because of a number of serious failures, mainly due to low validation and reliability and the inability to explore its vague concepts (difficulty in translating its concepts into operational definitions). In addition, although this approach was at first dominant, there was a further distancing from it, due to its pessimistic nature as regards to the human psyche (which led to the development of different and more optimistic theories).

Freud presented several models for understanding the human psyche. According to the topographical model, consciousness is divided into three levels (the conscious, the preconscious and the unconscious), with the most influential being the unconscious level. All the conflicts and desires that operate in the unconscious continue to affect the person, and in effect, their influence is greater than the conscious parts.

The other models presented by Freud were also very pessimistic:

In the dynamic model, the forces that drive the personality are referred to as instincts, which are divided into the Death Instinct (Thanatos) and the Life Instinct (Eros) (sometimes referred to as the sexual instinct, which translates into the energy known as libido). The Death Instinct impels man to aggression and self-destruction [1], whilst the Life (sexual) Instinct drives man to life.

In the structural model, the Id, the Ego and the Superego, compete with each other for the amount of available energy. If this is not enough, according to the psycho-sexual model every mental problem is related to an issue of sexual development at a certain age, since – according to this theory – a child’s main development is related to the preoccupation with satisfying his sexual fantasies.

The image of the human being that is thus created is that of an anxiety-ridden creature, who acts irrationally and unconsciously in order to satisfy animalistic instincts [2]. Furthermore, Freud held a deterministic opinion of man, that man has no free choice, and in fact has no influence on the world at all, but rather only responds to stimuli in his environment and to impulses that arise from the unconscious.

There is no doubt that at first glance the psychodynamic approach seems to be as far from Chassidism as East if far from West. But with a somewhat deeper examination it seems that precisely in it, are to be found principles which other approaches (which seem more similar to Chassidic theory) have completely neglected and which are essential to the understanding of the human psyche.

This is especially true of Freud’s view of the soul as a battleground between various forces, only one of which can be in control – ideas that are well known to all who have studied Tanya.

Comparing Forces and Parts of the Soul

A central motif in the Book of Tanya is that the driving force of man is the struggle of souls who wish to control the person’s three ‘garments’ (auxiliary powers, instruments of expression) – thought, speech and action. On the one hand is the divine soul, whose singular purpose is to fulfil the will of the Creator. On the other hand is the animal soul who craves all material desires, and in the middle is the natural soul – the soul that implements one of these two wishes. At any given time there is only one soul who comes to control the auxiliary powers, but the struggle is endless.

Freud, as we have seen, saw the human soul as composed of three parts – the id, the ego, and the superego:

There is only one principle that defines the id: the principle of pleasure. What interests the id is not what is right or acceptable but rather what is pleasing. It is easy to make the parallel between the id and the evil inclination; both the id and the evil inclination will bring destruction to man if they are the sole controlling forces.

From id develops [3] ego which is dominated by the reality principle and its role is to fulfil the desires of the id, but in an acceptable non-destructive manner. The natural soul also performs a similar function, since its task too is to actualise the desires of the animal soul that are essential for man’s existence.

The final stage in development is the superego, which corresponds to the divine soul. According to Freud, the superego is the conscience of the person which is acquired in the process of socialization and through the expectations of one’s parents and the environment. Here too, it is very easy to parallel superego with the divine soul.

The dynamism of the soul (the theory of which is called “psychodynamics”) is the transition of energy between the different parts of the personality. Each person has a limited amount of energy that can only be used in one of the three parts of the soul, and even a small change from one part to another can cause great changes in the person. The book of Tanya deals entirely with the struggle of the souls, when a simple transition between two parts can change the essence of the soul from one extreme to the other. For example, a person whose entire energy is invested in the superego will be on the level of a Tzaddik (righteous) or a Beinoni (intermediate), whereas a person who for but a moment transferred a very small amount of energy to the ego or to the id (e.g., when one is – for no legitimate reason – momentarily not occupied with the study of Torah), would, for the purpose of the discussion, be regarded a Rasha (wicked).

The struggle between the parts of the personality that is so important in Freud’s theory is at the centre of all psychopathology, the basis of which is the sense of anxiety which is suppressed by the various defence mechanisms. In short, man is in constant conflict between the unrealized desires of the id and the rigid demands of the superego, while the self in the midst feels much anxiety as a result. In order to deal with this anxiety, he uses defence mechanisms such as denial and repression, and transfers the feeling of anxiety to the unconscious. When the defence mechanisms fail to function properly, the person is in a problematic state of mind and responds with various pathologies.

This factor is very important for understanding the person according to the teachings of Chassidism, if one wishes to translate it into Chassidic language [4]. Countless times the Rebbe wrote to people who suffered from mental issues, that the solution is the observance of Torah and Mitzvos and to live life according to the Shulchan Aruch. This can be viewed in an abstract-spiritual way, but this can also be explained as a direct result of one’s mental state: If a person denies the commands of the superego (the divine soul) and allows the id (evil inclination) to act according to its desires (the principle of pleasure), then of course he will feel anxious. Even if he can avoid this feeling for a period of time (through the defence mechanisms), there comes a certain moment when they collapse, and then his behaviour will become dysfunctional.

How does one deal with the impulses of the id? Freud argued that all defence mechanisms are problematic at some level or another and the only proper defence mechanism is sublimation, in which negative energy is directed toward positive goals acceptable in society. In the teachings of Chassidism there is an emphasis on the use of the power of the animal soul for purposes of holiness, whether it involves the animal soul being subjugated (Iskafya) to harness its power for positive things, or whether it is the higher level of transformation (Is-hapcha) in which the soul itself is transformed to good. Either way – the concept of ”abundance comes by the strength of the ox (referring to the animal soul)” is intrinsic, and in fact corresponds to Freud’s theory sublimation [5].

Behavioural-Cognitive Theories

After a few decades in which psychodynamic theory dominated, psychologists began to challenge it, leading eventually to the emergence of the behavioural approach, and after that, as a result of criticism and other developments, cognitive ideas were added to form the main treatment method currently known as CBT – Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy.

Behavioural theory per se seems to be the method most distant from Chassidism, due to its refusal to recognize the inner world of man, coupled with its sole focus on observable, measurable, and quantifiable external behavioural processes. In fact, according to radical behaviourists such as Watson and Skinner, the superiority of man over animal is naught – literally. Therefore research can be performed on the behaviour of rats, dogs and pigeons and parallel and direct conclusions can be drawn as to human behaviour and there’s absolutely nothing defective in this. Thoughts, desires, feelings, memories, and other cognitions are a “black box” that cannot be explored and which there is no need to explore. In order to understand human behavior, it is sufficient to know a few simple principles of learning and conditioning and to look at one’s surroundings to identify the reinforcements and punishments that make one behave as one does.

Furthermore, the researchers of this approach also hold a deterministic view, that man has no free choice, and his actions are a direct result of the reinforcements in his environment. In addition, they are of the view that only positive knowledge (which can be objectively measured) is valid knowledge and therefore they of course negate the existence of the soul and the Creator of the world.

Nonetheless, there are some positive modifications in this approach compared to Freud’s pessimistic approach. First, according to this approach, man is capable of change, and therefore for every person there is the hope and prospect for development and growth. In addition, this approach does not have a negative and pessimistic view of the world, but rather a neutral and non-judgmental view (since personality is not determined by internal motives but rather by observable behaviours).

The Torah versus the Behaviourist Approach

Needless to say, the Torah in general and the teachings of Chassidism in particular totally disagree with this approach and see man as being essentially different from animals. Not only is there a recognition of man possessing the level of thought, but sometimes it is considered even more important than behaviour (the level of action) since thought is seen as one of the soul’s ‘garments’) auxiliary powers, instruments of expression). Therefore, the developments that added the cognitive dimension to the ‘study of the soul’ are very important in this respect, since they point to the nearing of the contemporary (behavioural-cognitive) approach to the ideas of Chassidism as described below.

At the same time, the behavioural-cognitive approach still lacks significant parts of Chassidic thought, since it contains no reference to internal conflicts such as a good inclination and a bad inclination. In other words – the behaviourist approach deals with the question of “how” rather than with the question of “what”; its primary concern is with the process rather than the content and therefore from its point of view there is no orderly reference to the human soul and personality [6].

Still, there are elements in the pure behavioural approach that are consistent with the principles of Chassidism. For example, the whole idea and system of reward and punishment has been empirically confirmed in countless studies that have examined the principles of learning theory, but they appear in the Torah as basic principles, both for man in general and for children. For example, the Rambam’s statement that children are given sweets in order to encourage them to learn, until they reach the stage where they become self-motivated and this is no longer necessary, will be explained in behavioural terms as a reinforcement programme whose goal is to encourage desirable behaviour so that it continue even after the cessation of the granting of reinforcements. In addition, the Chassidic idea of emphasizing reward instead of punishment (both for the encouragement of desirable behavior and for the elimination of undesirable behavior) has been confirmed in many studies which have proved that affirmative programs succeed in changing behavior far more than punishment.

In addition, the exclusive focus of the behavioural approach on environmental conditions is not in keeping with Chassidism, but the idea that the environment influences human behaviour is very consistent. It is stated as early as in the Mishnah that dwelling in an environment of Torah is an important consideration because of the understanding that man does not stand alone without any influence on him, but on the contrary. In the words of the Rambam in the Guide for the Perplexed, “Man is a social creature.” In many of his letters, the Rebbe refers to environmental conditions such as living in a Torah-observant area, studying in a Torah institution, and the undesirability of attending a university, because of the influence of the environment.

Think before you act (Last Made – First Planned)

The addition of cognitive components (to previous therapeutic and treatment methods) has brought the approach in its current version much closer to Chassidic ideas, since it places great emphasis on the faculty of thought and its influence on behaviour, which underlies the idea of “the mind is master”. Because of this, one often hears about the comparison between cognitive-behavioural therapy and Chassidism (but as mentioned, this is only a superficial comparison).

The early exponents of the cognitive approach disagreed with their predecessors, who espoused the behavioural approach, in two things. They argued that: 1) cognitions are of crucial importance in influencing human behaviour, and; 2) that thought could be investigated by sophisticated methods, which would be accepted not only as subjective truth but also by scientific methodology. We shall, of course, dwell on the first point.

In Tanya the Alter Rebbe explains that every action begins in the world of thought and emotion, and in countless places in Chassidism, the three garments – thought, speech and action – (auxiliary powers, instruments of expression) are discussed. According to Chassidus, thought is perceived both as the source of speech and action and as an end in itself. Man is able to monitor and change his thoughts, and they have a decisive influence not only on his behavior but on the world as well. Thus, for example, the Rebbe explains at length [7] the meaning behind the words of the Tzemach Tzedek: “Think good, it will be good,” since the thought of a Jew possesses power.

In addition, we also find that Judaism places high importance on thought, as in the case of “G-d combines good intention with deed” or “even if a person [merely] thinks of performing a precept but is forcibly prevented, Scriptures ascribes it to him as though he has performed it”.

Bandura, one of the pioneers of the cognitive system, focused on the processes that enable man to succeed, mainly self-efficacy. According to Bandura, the idea of ”I can succeed” is critical for a person to succeed, and so one can have talents but not succeed because his self-efficacy is low (and vice versa). Many times in Chassidus there’s a push for man’s recognition of his strengths and abilities, and a view that says G-d does not give a person a challenge he cannot overcome, etc. It seems that according to Chassidism man must invest time and energy to identify his hindering thought patterns and to replace them with more positive thinking patterns, which will directly affect his behaviour.

Another innovation of Bandura is the proposition of Reciprocal Determinism, with its three parts; the environment, man’s actions and cognitions, with each of the three influencing the remaining two. While the concept of Determinism is not fully compatible with the idea of free choice, in its present version it is a kind of model for examining the various influences, and less a statement that the effect must occur. Chassidus also sees all three components as influencing each other: Behaviour influences both the environment (“a Chosid creates an environment”) and cognitions (“hearts are drawn after the actions”), cognition naturally affects behaviour (as explained above) and the environment affects both behaviour and cognition (also as explained above).

Existential-Humanistic Theory

It is usual to see the emergence of existentialist and humanistic approaches as a response to the two approaches that preceded them – both the psychodynamic approach and the behavioural approach. The newer approaches related to internal motivations, impulses and desires (unlike the behavioural approach) but saw man as a positive being, as a creature striving for realisation, or transcendence of his human nature (an opposite approach from the psychodynamic approach). At the risk of simplification, perhaps we can say that the existential approach focuses on the question of human existence, and the humanistic approach focuses on the aspiration for self-realisation and growth. From this description it is possible to see how the new approaches moved closer to the direction of Chassidism, which deals extensively with the question of existence and fulfilment of personal potential.

Against Your Will You Live

According to Yalom, a person contends with four “givens” or ultimate concerns, (mortality, isolation, meaninglessness, and freedom) but the most important one is undoubtedly the concern, or anxiety, of existence (mortality), which is actually the fear of non-existence. Man knows that his time in this world is limited and this makes him anxious. This anxiety can be alleviated in several ways, but sometimes when faced with a reminder of the transience of life in this world, it forces him to deal with this anxiety and choose authentic life [8], instead of continuing to suppress the anxiety. Therefore, the reminder of death is actually positive because it is the only way to “shake out” the person and to make him face his choices courageously to ensure he makes the right ones.

There isn’t a great deal of reference to the subject of death itself in Chassidic doctrine, but there is a detailed reference to the question of existence from a slightly different perspective. However, in a number of places there is explicit reference to it, and the approach seems to be entirely consistent. In the Rebbe’s famous Chassidic discourse “Lo Sihiye Meshakeilah” [9] the Rebbe expounds on the Torah verse “I will fill the number of your days” explaining that the way to deal with the sometimes lethargy-causing tediousness of day to day routine is to remember the fact that one’s days are limited, which makes one focus on the fact that one must utilise one’s time properly. As Rabbi Yochanan ben Zakkai said before his passing, “I do not know in what way I am being led,” for when death approaches it is a powerful reminder of the anxiety of non-existence.

Another essential idea related to this approach is based on [Heidegger’s] existential philosophy of “Geworfenheit” (Thrownness), that man is “thrown into the world” and that his choice is only how to realize his possibilities. According to this theory, man does not choose whether to live or what will happen to him, but only how he lives the life into which he was “thrown”. This idea fits with the Mishnaic statement “Against your will you live” and as the Rebbe explains [10], the soul descends to this world against its will and suffers pain from the fact that it must deal with worldly matters and with evil present in this world. Therefore the mere contemplation of this, encourages one to utilise one’s every moment.

In this approach too (similar to the psychodynamic approach) there’s reference to anxiety and defence mechanisms, but the cause of the anxiety is not the unconscious inner conflicts, but rather the approaching death (or in Chassidic vernacular – the end of one’s mission in this world). When one represses the anxiety of existence, one loses the possibility of authentic life and ultimately suffers from psychopathology. Chassidism will of course agree with the general idea that the person who ignores the fact that his time in the world is limited to fulfilling his task through keeping Torah and Mitzvos will suffer from inner anxiety, which can only be reduced by courageously confronting reality, rather than its repression and escape to unsatisfactory solutions.

The apex of psychology’s progress towards the ideas of Chassidism is undoubtedly the treatment technique developed by Viktor Frankl, called “derefelction” or “reduction in self-examination.” It seeks first and foremost to dissuade the patient from focusing on himself where one of the ways to do this is to induce him to give of himself to others. The central critique of modern psychology is its exclusive preoccupation with the self, the ego; as opposed to the Chassidic approach of what man can contribute to the world and to others. Here, Frankl offers a method of therapy centred on precisely this point – the departure from self-focus and giving to others.

Scaling Needs

Thus, the existential approach requires man to overcome his nature and to choose an authentic life, similar to the approach of Chassidism. On the other hand, the humanistic approach is a little more modest, and it requires the person to utilize his potential for personal achievement. According to Rogers, man (and indeed every living thing, even a plant) is born with a natural tendency for development and fulfilment, and there is no need to do anything in order to develop in a positive manner, only to prevent disturbances in the process. Man is intrinsically good and the tendency for growth is inherent in him. For example, a flower does not need to be encouraged to flourish, and a baby does not need to be encouraged to start walking instead of crawling, rather once the natural tendency meets the conditions that allow it, it will occur spontaneously. This is an optimistic approach that corresponds to the theory of Chassidism that sees man as a creature created with a potential (purpose) to be actualised in this world, and was given the powers to do so, as long as he does not encounter impediments and hindrances.

According to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, the person deals first with basic needs (eating and drinking, safety and the need to be valued), and only when these needs are satisfied can he be free to attend to higher needs of self-realization. Although the hierarchy of needs itself has been criticized (which needs are to be classified as survival needs and which as growth needs) and also the assumption that one cannot deal with higher needs without one’s lower needs being satisfied, the needs hierarchy nonetheless provides a good framework for observing the personal mission of self-fulfilment. The lower needs in the hierarchy are also shared by animals, while the person must strive to fulfil needs beyond that. Chassidic theory will, of course, place at the top of the hierarchy the desire for self-realization by fulfilling the Torah and Mitzvos in the three areas of Torah, Avodah and Gemilut Chasadim.

The principles of humanism developed by Rogers also help to translate ideas from the teachings of Chassidism. Let us take as an example his recommendation for education based on the assumption that mental problems are caused by a discrepancy between the organic experience (obtained through an internal examination of what is good for him) and the need for positive self-esteem (as a continuation of positive evaluation of others).

In order to minimize the gap, Rogers argues that parents must communicate criticism to their children to make it clear that their actions are unacceptable, but at the same time not to direct it against them. “What you did is bad, but you are good”. This is the Chassidic approach to every Jew; “even though one sinned, he is still a Jew” and therefore even in a case when “one is deserving of rebuke” or in the rare case of being deserving of “hatred on account of their wickedness”, it will be directed only against the deed but under no circumstances against the sinful person himself.

Treatment of Anxiety According to the Chassidic approach

As we have seen, there is no one psychological system that fully complies with Chassidic teachings, but essential elements in each approach are consistent with it. Therefore, we will apply a few principles from each of the methods, and together we will adopt a treatment approach based on Chassidic theory, but one which utilises the different treatment principles.

From among all the approaches, Chassidic psychotherapy will of course begin with psychodynamics, to try to understand what is going on inside a person’s psyche, why his positive forces (the superego, the good inclination) do not find expression in the ego, and how the use of the defence mechanisms leads to anxiety. But unlike classical psychodynamic therapy, the focus will be not only on past development, but rather on the past as well as the present. In the course of “conversational treatment” the therapist will try to get to the root of the conflicts between the inner forces that the suffering person is dealing with, and thus release him from the symptoms – those that block him from fulfilling the Torah and Mitzvos, especially those that make him feel hopeless and worthless.

The treatment in the behavioural approach can be a traditional behavioural therapy, looking for factors in the environment that have taught the person inappropriate behaviour, and building a reinforcement program that will advance him in learning positive behaviour.

A very central part of the therapy will be the cognitive approach, since it will deal with learning methods to avoid negative thoughts (distraction – an idea mentioned countless times in the Rebbe’s letters), as well as imparting new and positive thoughts in which the idea that man is literally part of G-d and therefore inherently good, and the knowledge that man is G-d’s creation, and He is the one who takes care of him and provides all his needs. Additional techniques will be to learn how to develop faith and trust in G-d, especially in times of crisis.

In the existential approach, the therapist will try to encourage the patient to ask himself what is the purpose of his life in this world, as well as “remind him of the day of death”, in order to choose a more healthy and productive life instead of passing it in inaction.

In the humanistic approach, the therapist will try to ascertain whether there are unsatisfied lower needs in the hierarchy of needs which do not allow him to achieve self-realization.

One can also add to the these known treatment methods, elements from the more innovative approaches of Mindfulness, mainly through kosher meditation – both in practical instruction as how to perform mediation on the greatness of the Creator, in order to bring true serenity and tranquillity to the human soul and to use a kosher Transcendental Meditation programme developed by Torah observant experts.

It is important to note that, as the Rebbe’s letters indicate in many cases, Chassidic psychotherapy would well integrate with biochemical treatment. The Torah gave the doctor permission to heal, so cases of chemical imbalance in the brain are a matter for a specialist who can use the wisdom G-d gave him to prescribe medication that would help a person use his powers to improve his mental health.

Summary

It is clear from the above that even though every method of psychological therapy has its own virtues and disadvantages, Chassidus is the only method that contains all the virtues, but without the disadvantages, and is therefore best suited to be the choice psychological theory for comprehensively understanding the human soul. Hence it presents the possibility of creating a wide-ranging treatment system suitable for a variety of mental disorders.

The in-depth study of Chassidism will provide a clear understanding of the human psyche, along with practical therapeutic tools for professionals in the field of mental health, as well as for the ordinary person who wishes to use these tools himself, in order to live a fulfilling and meaningful life and overcome difficulties in all areas of life.

Appendices

Appendix A: Philosophy and Psychology

When we discuss the teachings of Chassidism as a psychological approach, we shall begin by comparing it to other psychological schools that currently dominate academia and psychotherapy.

These psychological doctrines are usually composed of three elements: psychological theory, research methodology, and treatment methods.

As an example, let’s look at the most famous doctrine of them all, Psychoanalysis. It is a comprehensive theory of the structure of the mind and man (including different structures for different parts of the personality), it is a research methodology (e.g. case studies), and it is a method of treatment (such as free association, dream analysis, and so on). Some of the psychological approaches are based on a philosophical method from which they derive their underlying ideas. For example, the existential approach is based on the existential philosophy that deals with the question of existence.

Chassidic teaching is first and foremost a comprehensive philosophical doctrine, and only then is it also an approach to understanding the human psyche. Therefore it is appropriate to treat it accordingly.

However, when we seek to use the ideas of Chassidic teaching for understanding the human psyche or treatment of mental health problems, one should consider the various elements that create a psychological approach: The fact that the Chassidic teaching does not contain a research methodology is not problematic [11]. This is because Chassidic philosophy is not based on empirical foundations but rather on spiritual foundations, the words of the living G-d [12]. The lack of a treatment method is also not a problem because as mentioned, we are dealing with Jewish philosophy. But the lack of an organized psychological theory is a problem for anyone who wants to use the great variety of Chassidic tools in psychotherapy (especially for the healthy person but also for the sick person).

It seems that the root of the problem for the absence of a well-organized Chassidic psychology theory lies in the fact that the theory of the psyche, which is based on the Tanya, includes various models of understanding the soul (e.g. the three garments, the ten dimensions, the two souls, etc.). But almost no systematic and comprehensive attempt was made to collect all the concepts to paint a clear and complete picture [13] of both mental health and psychopathology. Therefore, the person who wants to understand the structure of the mind and use the tools of Chassidic teaching, must learn to carefully review the Chassidic teachings, to integrate many different ideas, and then try to use the insights at his discretion [14].

Advances that enable a Chassidic treatment method

The downside is more evident in recent decades, as there is a significant shift in the world of psychology towards ideas that are increasingly compatible with the Chassidic approach to understanding the human psyche. This is especially evident with the shift from the dominant paradigm of psychodynamic ideas, that man is essentially evil and dominated by unconscious impulses of sex and aggression, to the existential and humanistic approaches that see man as inherently good, free-willed, and aspiring to achieve, to the establishment of the movement of “positive psychology” which raised such issues such as hope, happiness, spirituality and more. In addition, Freud saw religion and belief in G-d as problematic ideas that prevent people from living more freely, and sometimes as a source of neurosis (which he viewed as too strong a development of the “superego” that interferes with the proper operation of the ego), while existential and humanistic psychologists reversed the trend[15]. It is noteworthy to mention Victor Frankl [16] – an existential psychologist and Holocaust survivor – who completed the transformation when he stressed the importance of faith in a higher power [17].

In light of this nearing of psychology toward Jewish-Chassidic vision, the absence of a systematic initiative to describe the structure of the psyche according to the Tanya and the integration of its concepts into existing psychological approaches, becomes more evident. The present essay is a first attempt to translate some of the well-known concepts of the central psychological methods into Chassidic language, thus creating an initial framework into which additional concepts can be moulded and eventually categorized and presented as an orderly method. In order to present the unique possibilities inherent in such an approach, the method of psychological therapy in the mental disorders of anxiety as adapted to the theory of Chassidism is also presented [18] .

A last point: In the not-too-distant past, exponents of a given approach, barricaded themselves, each in their place, and refused to incorporate in their treatments any other guiding principles. For example, therapists and researchers from the psychodynamic approach have completely rejected the ideas of the behavioural approach, and so on, but now more and more therapists are adopting eclectic approaches – a combination of different principles [19]. This change of direction opens the door to the introduction of ideas from Chassidic teachings to the treatment rooms, if only as an addition to existing approaches to treatment that are well grounded in empirical research, especially in light of the fact that in Chassidus there are basic elements that appear in all the major psychological approaches, as we shall see below.

The opposite approach, which will also benefit from this, will be the use of usual treatment tools that will be translated into Chassidic language, which will benefit the treatment of those who grew up in the Chabad incubator and who are suspicious of psychological treatment methods.

Appendix B: Chassidism as Psychology

Why is Chassidism not Enough?

The first question to ask when we consider Chassidism as a psychological approach is, of course: Is Chassidism itself sufficient or should we ‘graze in foreign fields’ in order to adapt the existing methods of treatment to Chassidism?

At a public gathering (farbrengen) [20] in 5739 (1979), the Rebbe spoke about the phenomenon which began to spread rapidly in that period – Transcendental Meditation (TM). The Rebbe addressed the proven success of meditation in calming the mind and called for the creation of a Kosher meditation, to be developed by experts in the field of mental health who are also well versed in the Code of Jewish Law, in order to create a method that is both effective and does not contradict Halacha [21]. The Rebbe explained that for the ordinary person there is no need for this, as the answers to the life’s questions are engrained within the Torah and Mitzvos way of life, but for those who are sick and in need of help – further development is needed so that they can be cured of their condition.

In order to help a person suffering from mental problems, the Rebbe gave two conditions: 1) that the developers of the method and the therapists will be experts in the field; 2) that they should have Halachic knowledge. A therapist who meets only one of these criteria will not be able to address the burning problem of mental disorders: If he is an expert but not knowledgeable in Shulchan Aruch – it will cause serious problems [22] (to the point of transgressing the prohibition related to “accessories of idolatry”), and on the other hand if he knows the Halacha, but is not an expert in the field – he will be incapable of providing requisite expert remedies to people with mental health issues.

One can appreciate the importance the Rebbe put on the development of a response to mental health in a manner consistent with Jewish law, from the fact that in the Rebbe’s biography as recorded in the introduction to Hayom Yom, it appears as one of his the noteworthy efforts: “[the Rebbe] appeals to mental illness experts to complement their knowledge of “meditation” (specifically in a manner permitted halachically) and by so doing, benefit thousands of Jews who are in need of such treatment (who for the time being are wandering in misguided ways even so far as lapsing into the prohibition of ‘accessories of idolatry’, and when they will know that these treatments are available in a kosher manner, they will visit those doctors)”.

Kosher Psychology vs. Chassidic Psychology

In recent years, we have witnessed more and more therapists propagating methods of treatment according to the teachings of Chassidism in general and the Tanya in particular. Without going into the issue of the training of these therapists, there is a need to address the broader issue: Is Chassidus really a psychological method for treating mental disorders or is it a philosophy of spiritual life that suits a Jew with a healthy soul in order to serve G-d properly? Or, in other words, when we encounter a mental problem, should we turn to psychological treatment or Chassidic therapy?

As the Rebbe’s approach to the subject of meditation indicates, the Rebbe did not turn to the Chassidic scholars to develop a method of treatment based on the ideas of Chassidism. Rather, he turned to the professionals and asked them to adapt the existing methods of treatment to be permitted according to Jewish law. The Rebbe wanted to create a kosher psychology, but not a Chassidic psychology.

It seems that Chassidic doctrine is more a method relating to the soul’s structure and the forces acting in it, than a method of healing mental disorders. The Rebbe wanted to translate an existing method of psychological therapy that would be permitted according to Jewish law, for people suffering afflictions of the mind, whereas for healthy people he felt there was no need for this. Rather he referred them to the observance of Torah and Mitzvos as they are illuminated in the teachings of Chassidism. In his many letters, the Rebbe refers people in need of help and intervention, to professionals, and at the same time repeats again and again that living according to the Shulchan Aruch is the way to a healthy life.

Therefore, for the healthy person, translating Chassidic ideas to create tools for coping with the challenges of life is welcome, but there’s a long way from here to the presentation of Chassidism as a comprehensive therapeutic method (and apparently this is not the Rebbe’s approach). When a person suffers from schizophrenia, it is almost certain that a pharmacological treatment of the chemical imbalance in his brain is a better suited and more acceptable solution than an attempt to understand his mental condition through concepts of Chassidism. For this reason, we will not attempt to construct a new psychological therapeutic method based on Chassidism, but rather a combination of tools from familiar and well-known psychological approaches to fit the teachings of Chassidism, thus creating a “kosher psychology”, similar to the “kosher meditation” that the Rebbe sought to develop.

Appendix C: Recognition of Freudian Terms

To present the parallel between psychodynamic concepts to Chassidism, it is worth noting the Rebbe’s letter that gives a “green light” to use Freud’s controversial terms in order to explain questions in the understanding of the human soul according to Chassidic teachings [23]. This refers to Rebbe’s letter to Dr Velvel Green [24], in response to his question about Maimonides’ statement that one can force a person to divorce his wife – to “compel him until he says, I want to”: “There seems to be a clear contradiction here, if it is permissible for the divorce to be an enforced one, why is necessary that the person declare “I want”? And if and enforced divorce is invalid, what is the benefit of declaring “I want” under duress?”

After the Rebbe answers the question, he adds:

“If we are to put the above in contemporary terms: The conscious state of a Jew may be influenced by external factors, to the point of causing a state of consciousness, even behaviour, that are contrary to his subconscious, the essential nature of the Jew. When these external pressures are removed, it does not constitute a change that is in contravention of his essential nature; on the contrary, it is merely a revival of his innate and true nature.

“For a person with a background like yours it is superfluous to point out that none of this should be construed as affirming other aspects of Freudian theory which imply that the human psyche is dominated mainly by lust etc. since these ideas are contrary to the conception of the Torah, which views man as essentially good. The only similarity is in the general idea that human nature consists of different layers and sub-layers, especially when it comes to a Jew”.

In this letter the Rebbe takes a far-reaching step when he refers to the unconscious according to Freud. The very recognition of unconscious processes is not new, and certainly Freud was not the first to propose it. The novelty of psychoanalytic theory is the recognition that it is the unconscious forces that determine a significant part of our behaviour. In this case, it is not enough to say that the Jewish subconscious wants to fulfil Torah and Mitzvos. Rather, it is necessary to say that the true essence of human nature is the level of the unconscious, and when the concealing external pressures are removed, the truth is revealed.

Thus the Rebbe shows us a general way of relating to various psychological methods, first and foremost Freud’s theory: “Eat the inside of the fruit – and discarded its peel”. There is no impediment to using contemporary terms to explain Chassidic ideas, and on the other hand, this does not confirm other parts of these theories, which contradict Torah and Chassidism.

Notes and sources

[1] Recently (in the Memento for the Blank-Wagner wedding) a letter of Rabbi Dr Nissan Mindel to the Rebbe was published, asking whether it is possible to say that the drive for aggression according to Freud is in fact the parallel to the concept of the animal soul in Chassidism. It is a pity that the Rebbe’s response to the question was not published, which could have shed light on the subject.

[2] It is not in vain that Freud is referred to as continuing Copernicus’ and Darwin’s path, when, following the argument that the earth is not the centre of creation and man is not the crown of creation, Freud claims that even the human soul is not at all under one’s control.

[3] It is interesting to note that even according to Jewish law, man is born first of all with the components of the animal soul, and only afterwards (at the age of Bar Mitzvah) does the entire divine soul develop. See the Alter Rebbe’s Shulchan Aruch Last Version 4:2. However, the Chassidic approach is more similar to newer psychodynamic theories, which claim that the ego has its own reservoir of energy, and it does not evolve out of the id.

[4] Similar to the experiment conducted by Dollard and Miller in explaining psychodynamic concepts using terms from Hall’s theory of learning.

[5] In addition to this intrinsic matter, the intra-psychic conflict in controlling the amount of energy, other parallel concepts can be found. Recall Freud argued that man is overwhelmingly influenced by unconscious content, and one way to expose the unconscious is through the dream. According to Freud, during the dream man’s defences are less powerful, and it is then that content can penetrate from the unconscious part to consciousness. Psychoanalysts therefore attach great importance to dreams (in psychoanalysis there is a difference between the manifest content of the dream and the hidden content, but we will not dwell on it in this framework). The Rebbe spoke about the fact that since the real identity and essence of yeshiva students is Torah, it is possible to see this in the fact that even in the middle of their sleep they dream of Torah matters and debates of Torah (Private Audience with Students, Tishrei 5752, Hitvaaduyot 5752 vol. 1 pp. 213). In other words, during the dream the true personality is revealed without defences.

Recall Freud argued that the impulses repressed to the unconscious are constantly trying to find their way out, and that they affect our behaviour. He therefore explained that actions that seem to have occurred in error (which he called “acts of failure” and many of which are now known as “Freudian slips” in his name) are not errors, but are simply another way of breaking into the conscious. Therefore, a slip of the tongue that was uttered by mistake is actually a hint of the person’s true intention… It is the way the subconscious expresses itself. A similar approach can be found according to Chassidic doctrine, which explains why even a person who committed a transgression unwittingly must seek atonement and offer a korban (sacrificial offering), since even in a situation of error, the fact that a Jew is capable of committing an offense shows that his condition is not as it should be, for if the person was really far from the offense, he would not fail.

In the words of the Rebbe: “The things that man does automatically, inadvertently and unintentionally, show his essence, what he is preoccupied with and of what he derives pleasure” (Likutei Sichot vol. 3 p. 944).

[6] For this reason, some do not include the behavioural-cognitive approach with other personal theories because it lacks the internal component, and instead classify it as a learning theory.

[7] Likutei Sichot vol. 36 pp. 1.

[8] The term “authenticity” according to existential philosophy parallels the term “truth” in its usual sense, because of the phenomenological approach that there is no point in seeking universal truth, but only what is the truth for each person himself. Although this subjective approach is not consistent with Chassidic theory, the idea that one must live a true life still stands.

[9] Sefer Hamaamarim 5712.

[10] Torat Menachem 5714, pp. 192-195

[11] In addition, even if it would be possible to subject Chassidism to empirical study, there will be a fundamental reason not to do so; in order not to cause the spiritual knowledge to be based on empirical data, similar to the opposition of the existential approaches to the scientific investigation of subjective experiences, so as to leave them to be phenomenological. Of course, the doctrine of Chassidism will disagree with the principle that only positive knowledge is valid, and instead determines that only knowledge that comes from the Torah itself has real value.

[12] Another methodological problem is how to explore abstract concepts that occur inside the soul. But impressive advances in this field in the study of concepts in existential psychology suggest that with sufficient will and creativity, many of the concepts of Chassidism (although not all of them) can be empirically tested. For example, the concept of “existential anxiety” was investigated in terms of its status and it was confirmed as an influence on overt behaviour. See below for the comparable concept in Chassidism.

[13] It is noteworthy to mention Dr Baruch Kahana’s book “שבירה ותיקון – מודל חסידי לפסיכולוגיה קלינית Breaking and Repair – A Chassidic Model of Clinical Psychology.” Another book that took an important step in this direction is ”שיחות עם בעל התניא Conversations with the Ba’al HaTanya” by Dr Yechiel Harari, but this is a book intended more for the wider public and as such is more a self-help book than a work presenting an orderly method for therapeutic use.

[14] It can be said that this is the general Jewish approach, and few are the exceptions who dared to change this trend. In general, it can be said that Judaism excels as a holistic approach in which there is no direct linear progression from the starting point and on (as is the case with Maimonides’ Yad Hachazakah which was ground-breaking by any standard), but rather as a comprehensive and all-encompassing view. Thus, for example, the Mishnah begins with “From when is the Shema to be read?” I.e., it assumes that the learner already knows a large part of the information and does not begin from the base towards the summit. This method will be effective in people with holistic thinking, but will make it difficult for people with logical thinking, and some even claim that this is the difference between the Semitic languages which are written right-to-left and non-vowelized and other languages written from left to right and are vowelized (Rabbi Jonathan Sachs, The Great Partnership 2011).

[15] From a historical perspective, Dr Carl Jung preceded and considered as being of the founding generation of psychoanalysis, but he distanced himself from Freud’s approach and included spiritual themes in his own approach. For example, the idea of withdrawal from alcoholism by spiritual awakening was originally his, and in a letter to Bill Wilson (founder of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA)) He notes that the thirst for alcohol is parallel to thirst for G-d, and quotes the verse from Tehilim: “ As a hart cries longingly for rivulets of water, so does my soul cry longingly to You, O G-d.

[16] See the words of Rabbi Ya’akov Biderman “a message from the Rebbe, just before Dr Frankl gave up ”

[17] It is possible that it is to him (or to Dr Carl Jung) that the Rebbe referred when he wrote: “And especially since one professor found the courage to declare and announce that (contrary to the method of the founder of this well-known treatment), faith in Hashem and a religious inclination in general etc. etc. which brings content into life, is one of the most effective things for curing etc.” (Igrot Kodesh vol. 22 pp. 227).

[18] Although Chassidic theory is more suited for people with a healthy psyche seeking further improvement, and less to organic disorders.

[19] Whether in integrative approaches that combine tools from different schools, such as behavioural-cognitive therapy, or in the combination of opposite approaches, such as the dialectical behavioural therapy developed by Marsha Linehan for the treatment of borderline personality disorder.

[20] Rebbe’s Talk, Tammuz 5739.

[21] The Rebbe suggested to Dr Yehuda Landes, who was then living in California, to recruit a group of doctors specializing in neurology and psychiatry to adopt kosher meditative techniques of therapeutic value for relaxation and release from mental stress. And responding to an expert, the Rebbe clarified that this refers to the development of a method similar to Transcendental Meditation, and not just to “contemplation (hitbonenut)” – a basic concept in the teachings of Chassidism (Likutei Sichot vol. 36 pp. 335).

[22] To point to the Rebbe’s letter: “Regarding his letter that the above person is in the care of a doctor who deals with mental health, although it is not so clear to which doctor he refers, generally to our dismay, there is a particular type among them who begin the therapy by speaking against G-d, the honour of heaven and the honour of parents etc., and examination and inquiry is needed to determine the value of its benefit, even if it is important, whether the damage later on does not supersede this” (Igrot Kodesh vol. 22 pp 227).

[23] Interestingly, the 5th Rebbe, the Rebbe Rashab (Rabbi Shalom DovBer) turned to Freud for treatment, but his letter on the subject seems to indicate that the reason was his treatment of the nervous system in his hand (Freud was a trained doctor who specializes in the area of the nervous system – Neurology).

[24] Dated 21st Sivan 572. Published in the book “פרופ’ גרין שלום וברכה – Prof. Green Shalom and Bracha” pp. 48.

713

Join ChabadInfo's News Roundup and alerts for the HOTTEST Chabad news and updates!